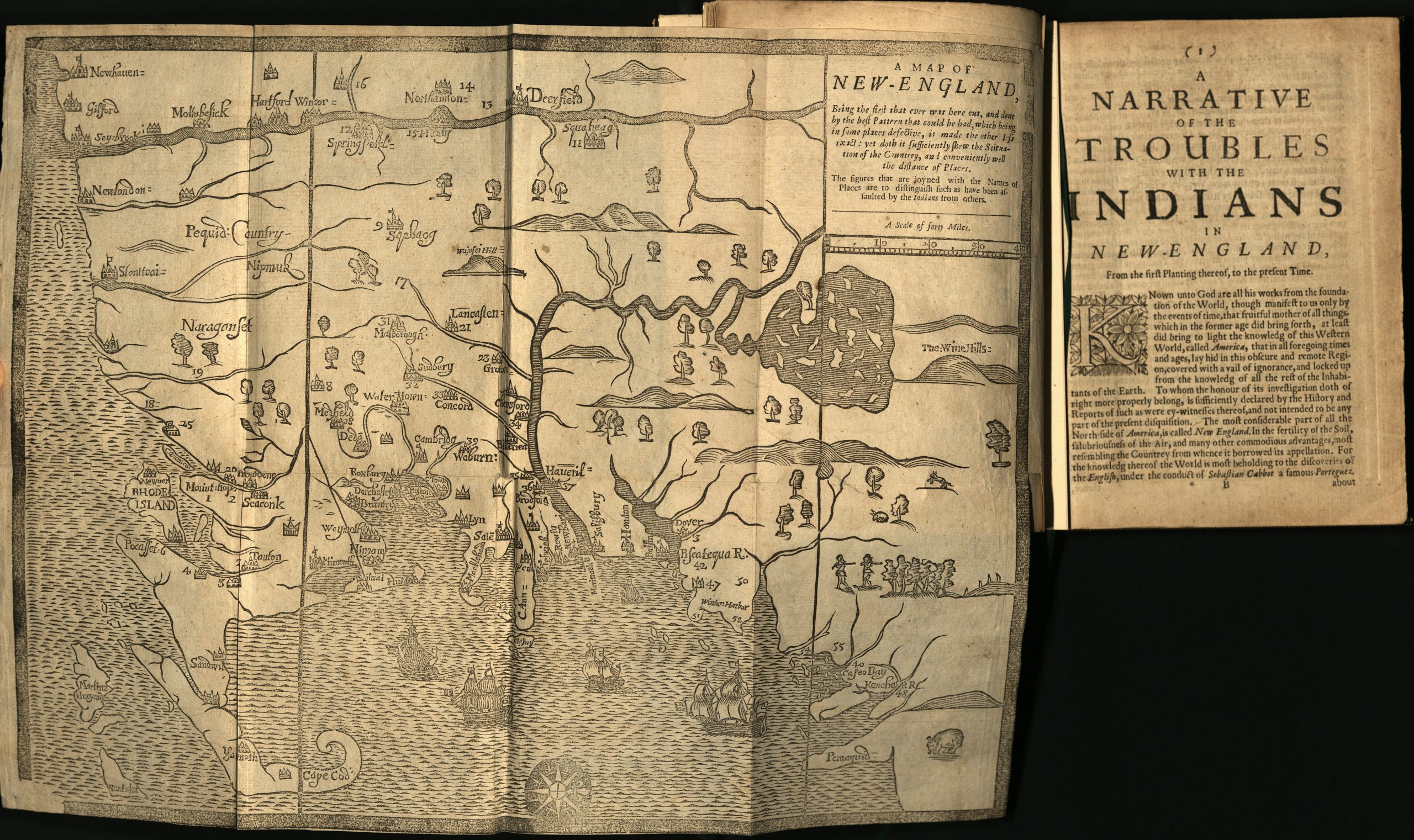

The Present State of New-England: Being a Narrative of the Troubles with the Indians in New-England, from the First Planting Thereof in the Year 1607, to This Present Year 1677: But Chiefly of the Late Troubles in the Two Last Years 1675, and 1676. : To Which Is Added a Discourse About the War with the Pequods in the Year 1637.

Hubbard, William, Thomas Parkhurst, Simon Bradstreet, Daniel Denison, and Roger L’Estrange

1676, London

Printed for Tho. Parkhurst, at the Bible and Three Crowns in Cheapside, near Mercers Chappel, and at the Bible on London-Bridg.

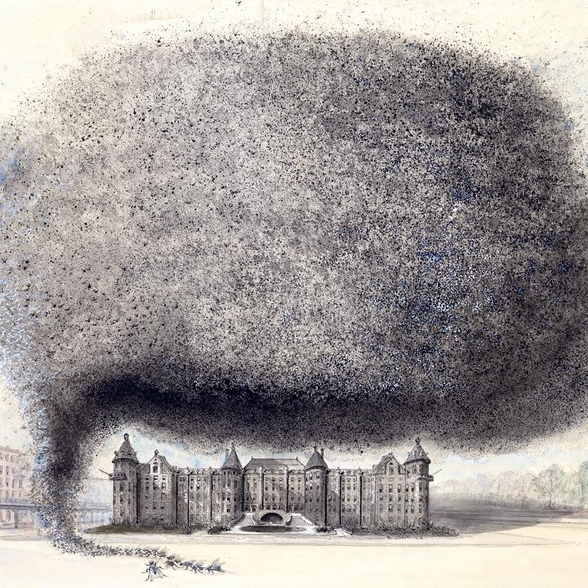

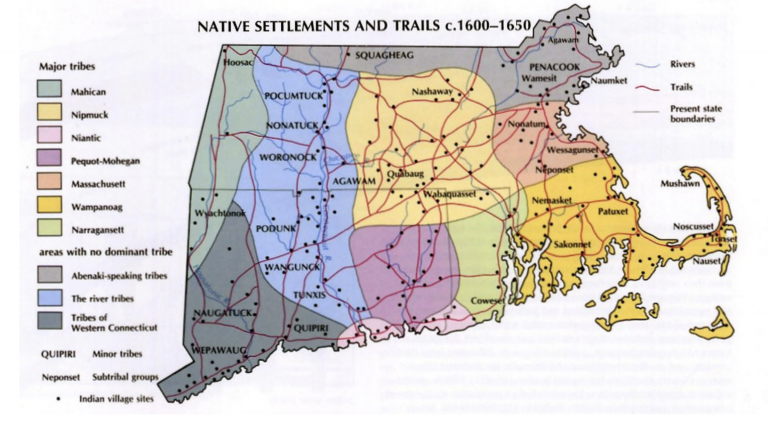

This woodcut map of New England was created by woodcutter and printer John Foster in 1677. It was created to accompany the Minister of Ipswich, William Hubbard’s A Narrative of the Troubles with Indians in New England, From the Planting Thereof, to the Present Time, as a visual aid. Historians believe this map to be the first ever printed in the New World.

The author William Hubbard (1621–1704) came to write his “narrative” after participating in King Philip’s War. King Philip was the English-given name of the Wampanoag sachem (or leader) Metacom or Metacomet. During the years 1675 and 1676, war broke out between the Wampanoag people and the settlers of Plymouth Colony. The war devastated not only the Wampanoag people, but also the Narragansett people. During the Pequot War (1637) the Narragansett, longtime enemies of the Pequot, fought alongside the English against the Pequot. In the aftermath of the war, the Narragansett strove to remain neutral despite ongoing conflict. In 1675, sachem Metacom sent Wampanoag women, children, and elders to shelter with the Narragansett, hoping their neutrality and their historical alliance with the English would ensure his people’s safety. By December of 1765, the English established a military force including English, Pequot, and Mohegan warriors to storm Narragansett fortifications. Their aim was to prevent a military alliance between the Wampanoag and Narragansett. This culminated in The Great Swamp Massacre. An estimated 1,000 people were killed during the attack, including about 400 Wampanoag women, children, and elders. Not surprisingly, the massacre incited the Narragansett to join the war in alliance with sachem Metacom and the Wampanoag people—the very alliance the English were attempting to prevent.

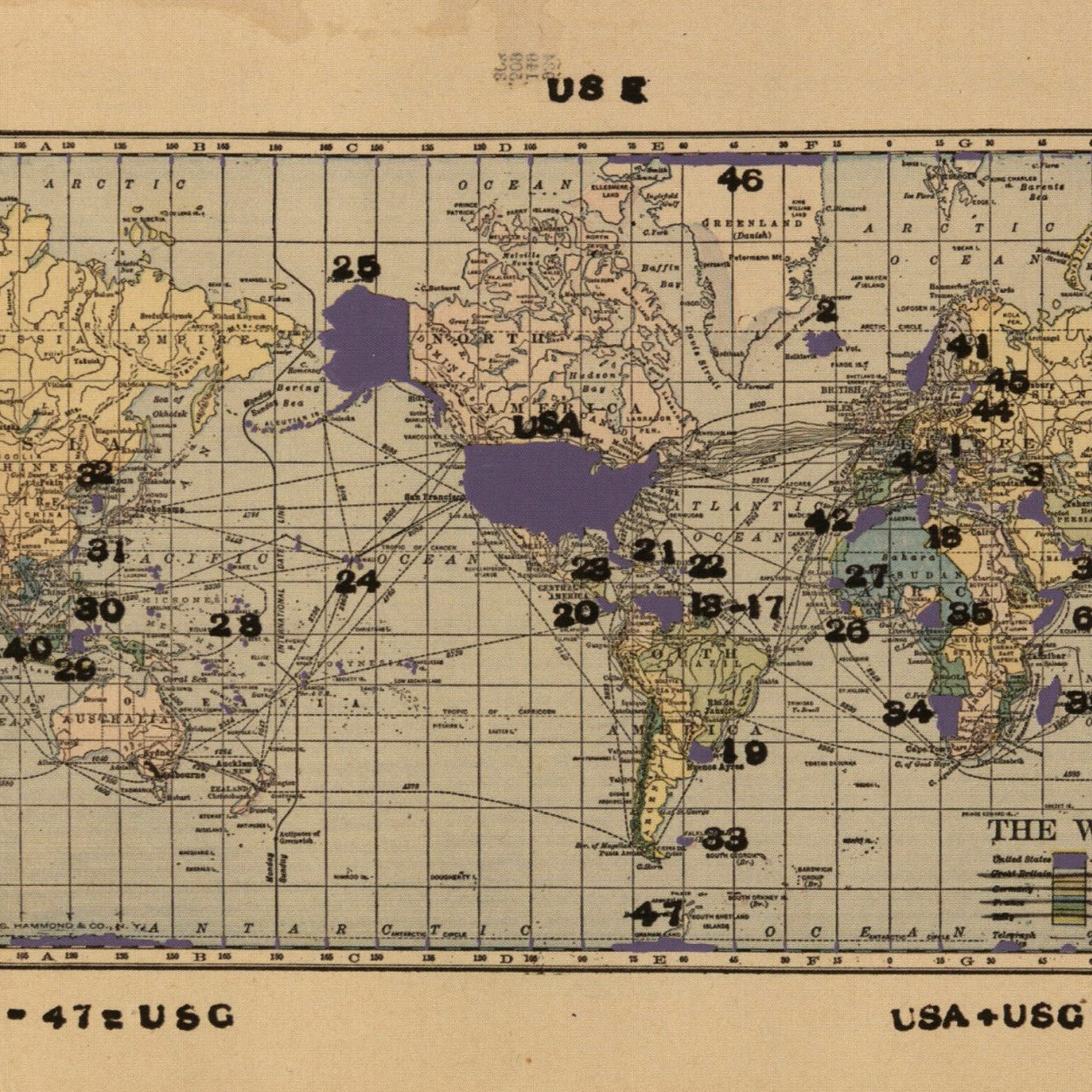

This map was crafted to provide readers with geographical information concerning conflicts preceding and including King Philip’s War. Yet, there are several visual choices of note that suggest that geographic locating was perhaps only one of several goals for this map. For example, North is orientated to the right of the map. Then, if one looks closely, one might notice there are numbers scattered throughout the map. These numbers identify the reported locations of battles and massacres described by Hubbard’s narrative. Thus, the purpose of the map—to mark important locations according to Hubbard’s tale—influenced the design of the map rather than accurately represent the geography. As a result, when comparing this map to present-day depictions, Connecticut appears strangely shrunken whereas Martha’s Vineyard, Rhode Island, and the Boston area include sprawling territories and rich details. One possible explanation for the warped appearance is that much of King Philip’s War was fought along the shores of Rhode Island and Martha’s Vineyard; therefore, Foster sought to include those areas in great detail in order to appropriately mark out battlefields. Alternatively, perhaps the effort to squeeze in the stretch of Cape Cod skewed the Foster’s ratios.

Foster’s work reminds us that maps are always an artistic interpretation of information (whether that information is generated by satellite imaging or word of mouth). As we see in Enrique Chagoya’s “Road Map,” maps do not simply record our knowledge about the world; they generate it.

Relatedly, Hubbard prefaces his tale with a long-winded discussion of the difference between “history” and “narrative.” He writes in the preface, “[T]he matter of fact therein related (being rather Massacres, barbarous inhumane outrages, than acts of hostility, or valiant achievement) no more deserve the name of a War, than the report of them the title of an History; therefore I contented myself with a Narrative.” Hubbard’s narrative was widely circulated in England and New England, and it enjoyed a resurgence in popularity in the early 19th century with the establishment of the Massachusetts Historical Society and other community institutions committed to cultivating and preserving American History. Though Hubbard cautions readers against understanding his catalog as a reporting of historical facts, the paucity of recorded knowledge about the pre-Revolutionary New World means that we have relied on Hubbard’s work as history.

Written by Katrina Kish with assistance from Kristin Eshelman

![Howard Russell Butler's [Hydrogen prominences]](https://futureoftruth.media.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2921/2023/01/k6584-square.jpg)