Henry Fairfield Osborn’s work with the AMNH began in 1891 when he was appointed Mammal Paleontologist. He later served as AMNH President from 1908–1933. During his tenure at the AMNH, Osborn was a respected and influential scientist, researcher, and political activist.

This unique letter opener was gifted to Osborn by his wife, author and biographer Lucritia Thatcher Perry, upon his appointment as AMNH President. The letter opener was made by Tiffany & Co., an American luxury jewelry company founded in 1837 by Charles Lewis Tiffany and John B. Young. The letter opener might be a product of Design Director Louis Comfort created during Tiffany's art nouveau period.

The fossil featured at the head of the opener was one that was discovered in the Dakota Formation. The Dakota Formation is a sedimentary rock deposit which stretches all the way across the North American continent, from British Columbia to the Great Plains. Its colorful formations preserved many organisms, including fossilized leaves. UConn houses its own collection of fossils from the Dakota Formation, largely built and maintained by Professor Henry N. Andrews and his students.

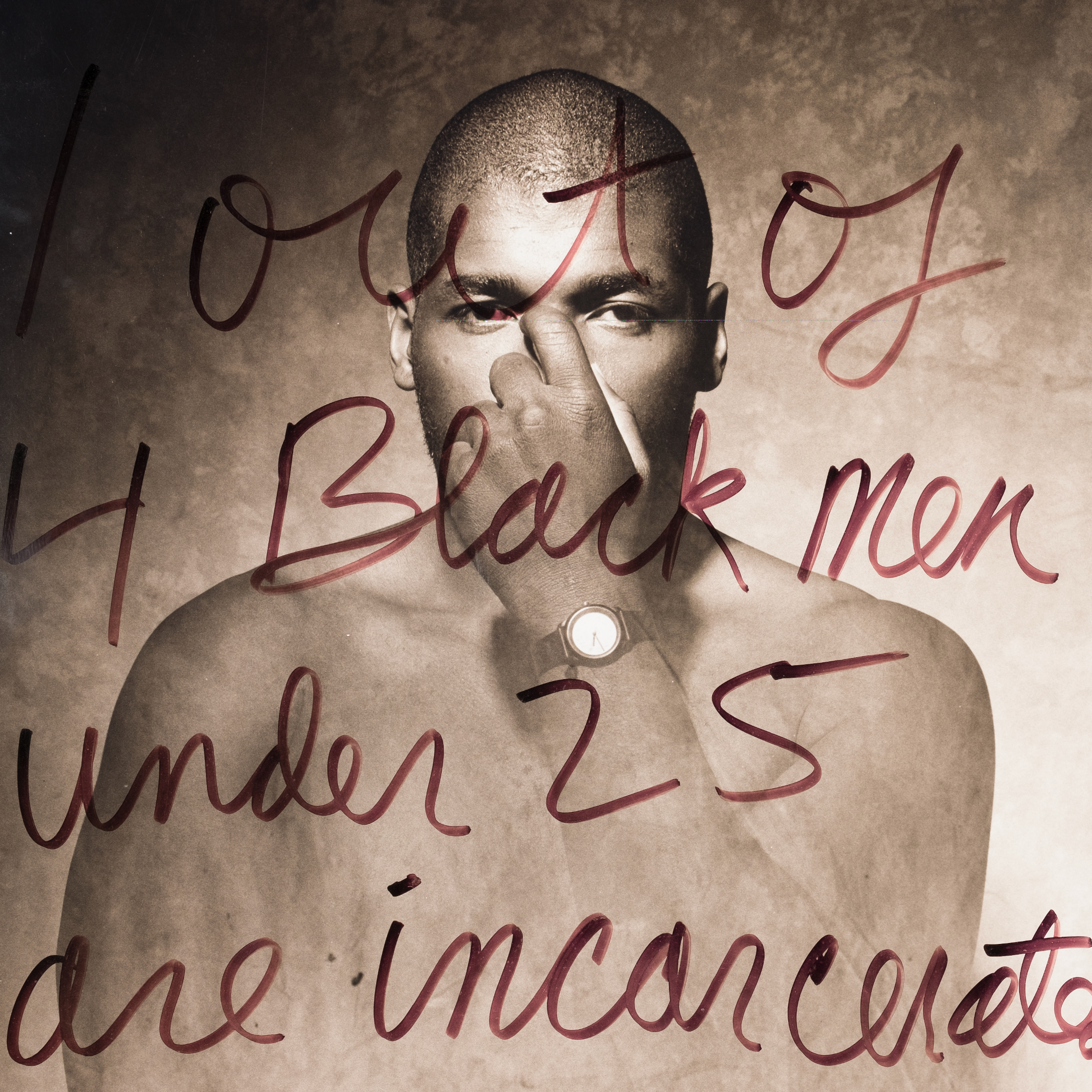

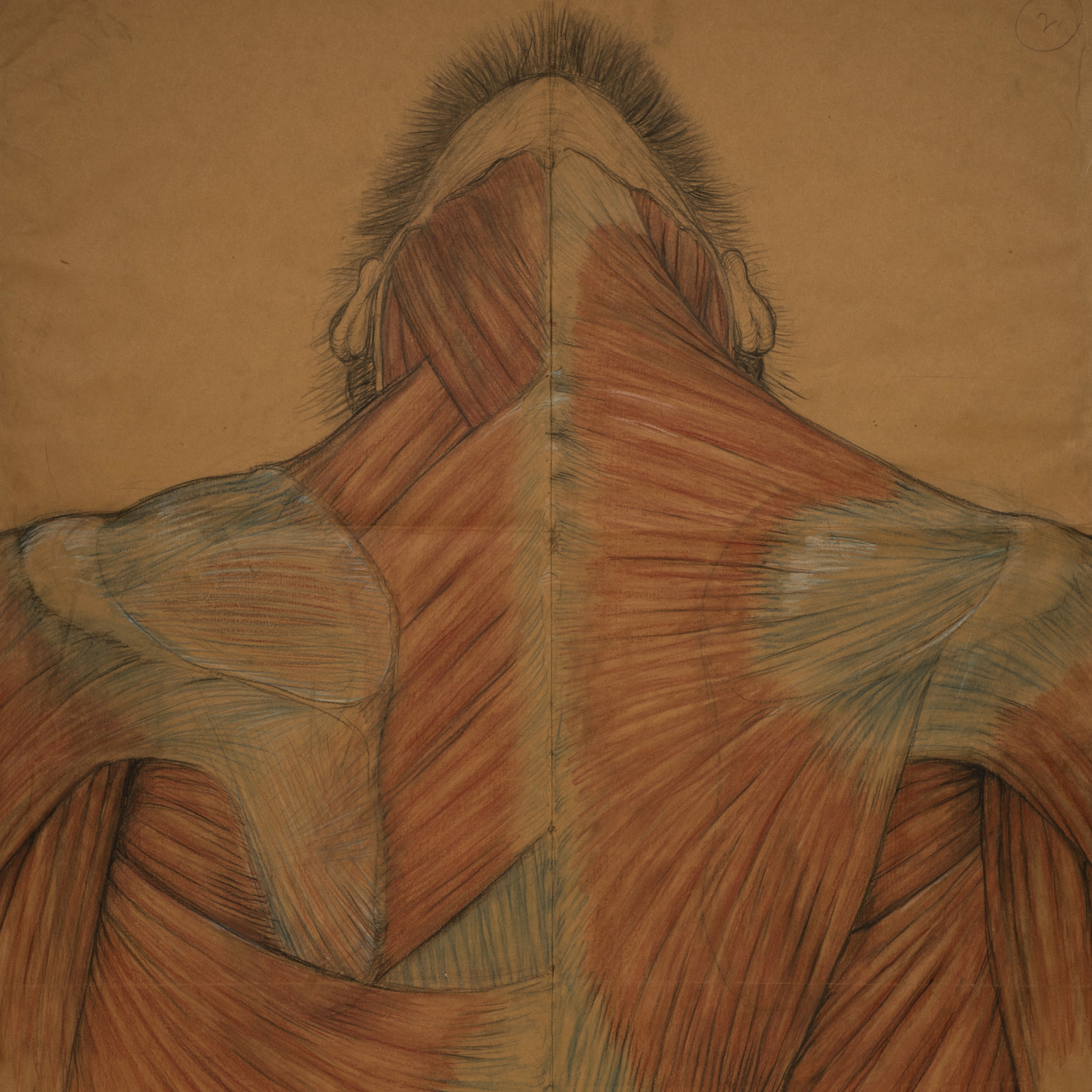

While this letter opener may strike contemporary viewers as merely a decorative and benign trinket from a wife in honor of a promotion, this fossil impression reflects the larger theoretical vision that Osborn was dedicated to, and a vision that he used museum resources and floor space to promote. Osborn was committed to proving scientifically that there were fundamental differences in races. He worked to discover evidence of human evolutionary origins, including evidence of biologically different races. Osborn believed humans of different races evolved from different ancestors in different regions of the world and theorized that human races with fewer regionally particular biological adaptations were best suited for survival. Of course, Osborn believed “Nordic” races were the least specially adapted and therefore the genetically superior race. Conversely, African and Asian peoples were thereby considered genetically inferior due to their supposed regional adaptations.

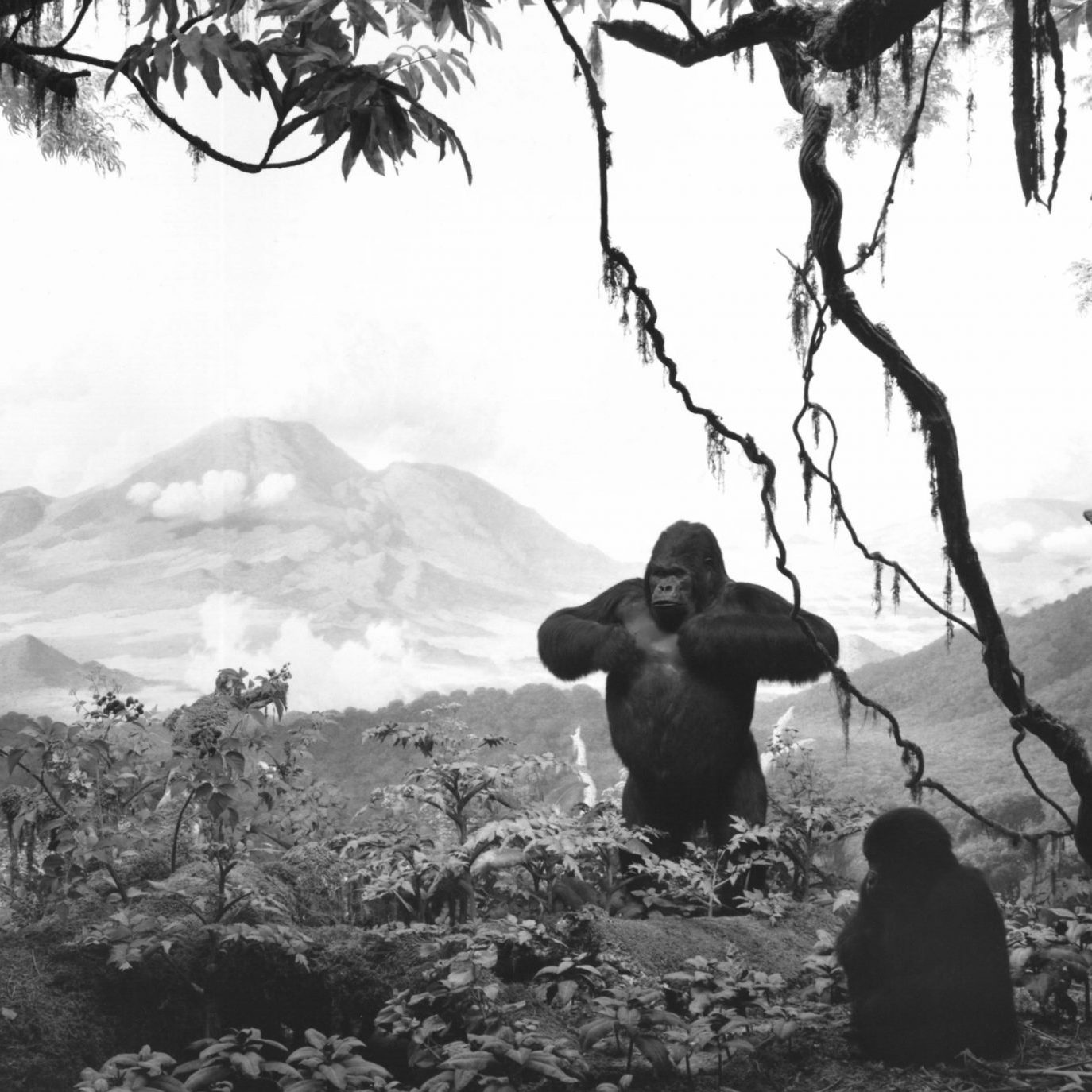

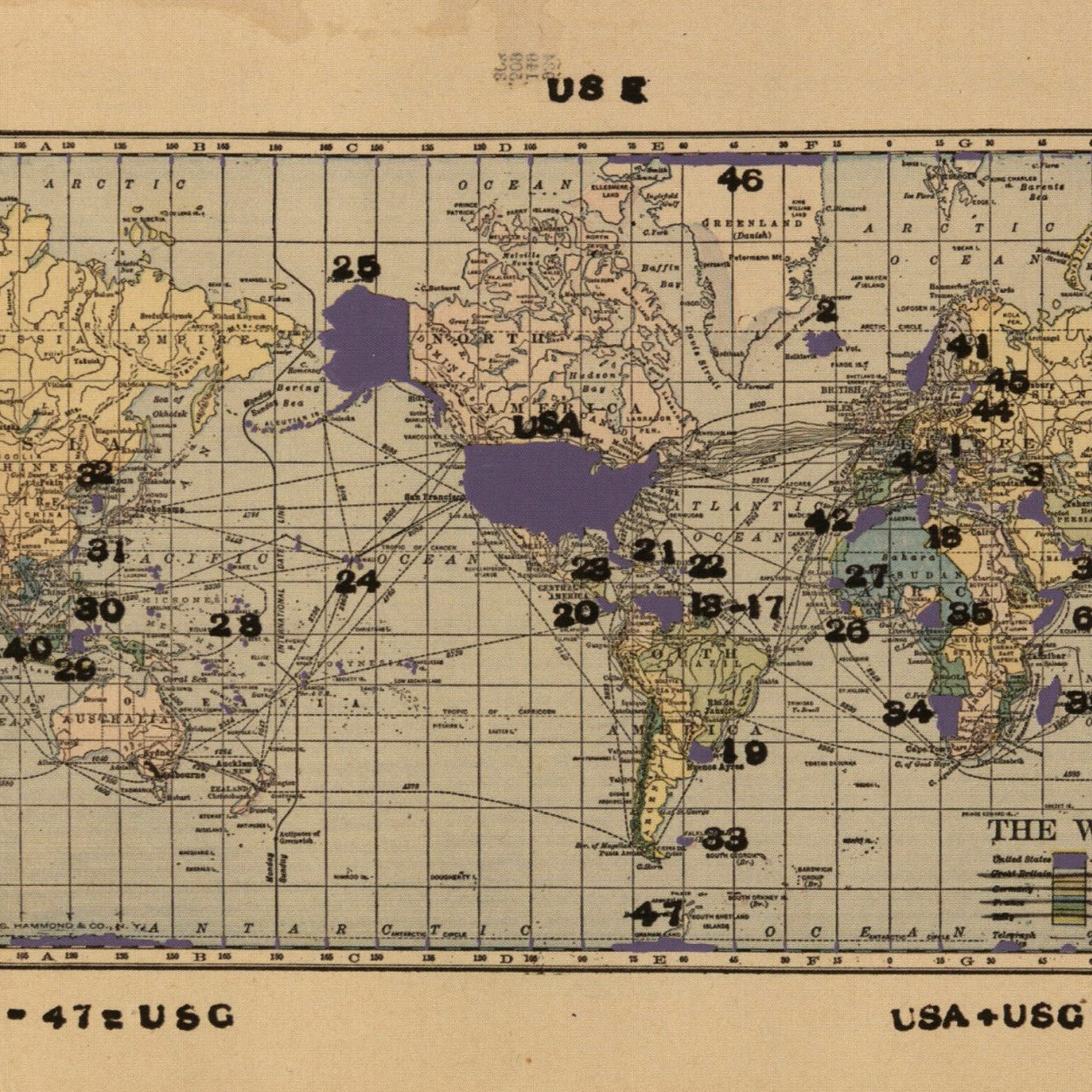

As President, Osborn oversaw multiple AMNH research expeditions, including a journey to the Gobi Desert in the steppes of Mongolia. Osborn believed that the Gobi expeditions would uncover the fossil remains of early humans who evolved locally in Asia to support his theory of biologically distinct human races. It did not. Instead, the team uncovered new animal fossils, including the first discovered dinosaur eggs, and Cenozoic mammal fossils.

This letter opener was a bespoke Tiffany set, created to highlight Osborn’s discoveries and remind him, as he worked through the day, of the very material contributions he made to the museum. It is interesting to consider how small objects like this, an expensive, delicate, and fashionable work, visually inspired and maintained Osborn’s daily labors, and perhaps inspired him to keep his focus, keep working, keep exploring his fantasies of “proving” racial difference. While not scientific per se, it is important to consider how objects and images influence those that then finance, promote, and lead scientific knowledge.

Written by Katrina Kish

![Howard Russell Butler's [Hydrogen prominences]](https://futureoftruth.media.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2921/2023/01/k6584-square.jpg)