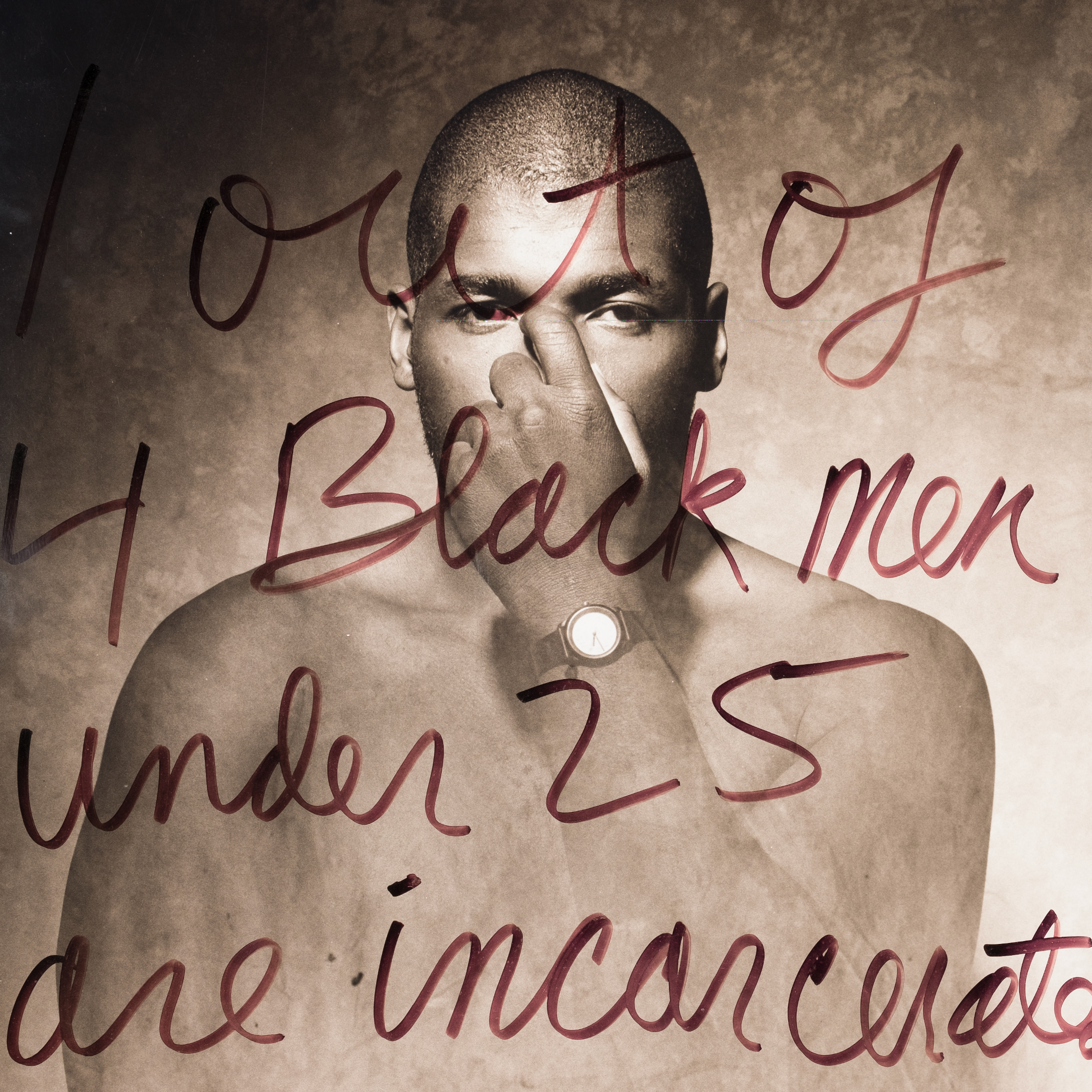

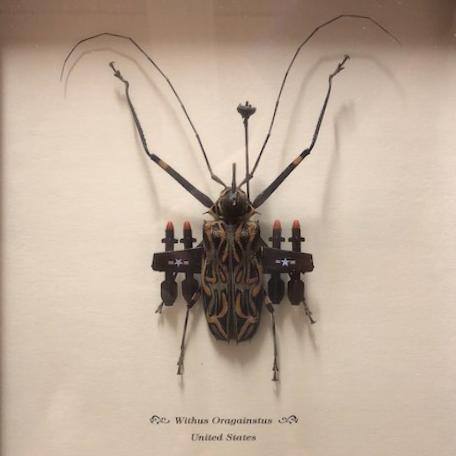

Don’t Fade Me Out #2

(1 out of 4 Black men under 25 are incarcerated)

Todd Gray

1996

24 x 20”

Chromogenic print with ink

William Benton Museum of Art, Louise Crombie Beach Memorial Fund

The long career of American photographer Todd Gray has turned on several of the same themes: race, masculinity, diaspora, and power. His sensitivity as an artist to these issues earned him the position of Michael Jackson’s personal photographer in 1979–83, at the height of Jackson’s fame, and has continued to shape his oeuvre in the years since. His work has increasingly taken an interest in Black diasporic history, coming to terms with its archival footprints and lasting resonances.

Don’t Fade Me Out #2 skillfully knots together several strands of Gray’s immense oeuvre and reckons with the effects of U.S. mass incarceration on Black men.

Scrawled across the photo is the shocking, though sadly familiar, statistic, “1 out of 4 Black men under 25 are incarcerated.” This statistical view of the U.S. incarceral system’s targeting of Black men might appear impersonal and calculated, merely a data point. Yet, Gray’s handwriting adds a personal connection between the artist, a Black man himself, and the statistic. This statistic does not represent mere information, but people’s lives.

This insistence on the human obscured by the dehumanizing force of racism echoes through the photograph itself. The photo resembles a mug shot, a visual staple of the carceral system that circulates inside and outside of vast criminal databases. Photographs have often been used to categorize people into types, such as “criminals,” and serve as evidence for eugenics and discriminatory social policies. Hence, as with the statistic, this photographic cataloging of prisoners—who are disproportionately Black men—cannot be understood as a neutral bureaucratic activity. As award-winning art historian Nicole Fleetwood argues in her book Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration (2020):

Representation was an essential tool to support tough crime policies and punitive sentencing. Assaultive and dehumanizing images, such as “wanted” posters, arrest photographs, crime-scene images, and mug shots circulated frequently in local and national media and reinforced the practices of aggressive policing and dominant notions of black criminality.

In short, these dehumanizing media license the political policies and cultural attitudes that sanction the racist activities of the carceral state. Gray presses on the assumptions of the mug shot, particularly its claim to represent an individual criminal. The subject’s hand obscures his mouth, turning him from the identifiable person of a mug shot into merely an example of one of the countless Black men kept in the U.S. incarceral system.

In this act of covering and silencing, the subject further calls attention to his wristwatch. Closer observation reveals that the watch has no numbers on its face. It can only witness the passage of time but cannot measure it. This indefinite temporality opposes the legal notion of a jail sentence—a finite amount of time—and suggests instead the collective, ceaseless time of Black imprisonment.

In turning between the personal and the impersonal, Gray’s photograph enjoins us to consider both the impersonal, systemic violence of incarceration and the actual human lives locked within this system and obscured within representational ways of knowing.

Written by Daniel Pfeiffer

![Howard Russell Butler's [Hydrogen prominences]](https://futureoftruth.media.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2921/2023/01/k6584-square.jpg)