Suez

Frederic Leighton

1880

Oil on canvas

22 1/8 x 18 1/8”

William Benton Museum of Art, Gift of Joseph F. McCrindle.

The lone ship floating through the Suez Canal in Frederic Leighton’s Suez (1880) betrays the frenzied economic activity between the East and the West that the creation of the canal through Egypt a decade earlier, in 1869, enabled. Trade between Europe and Asia had existed for centuries, thanks to the Silk Road, but the Suez Canal opened a waterway that greatly increased the rate of trade in the 19th century, and, as its obstruction in early 2021 demonstrated, the canal remains a crucial node in the global supply chain. The 19th-century European fascination with the so-called Orient created a large consumer demand, particularly among the bourgeoisie and the aristocracy, for luxury goods from Asia, including silk, spices, and furniture. More than that, the Suez Canal facilitated the circulation of culture, religion, and ideas from the East and interested intellectuals, artists, and ordinary people alike.

Leighton, a popular artist in his day, offers a snapshot in his painting of the former boundary between the East and the West. He balances an easily recognizable image of a ship, with two small boats and a few people surrounding it, with a dreamy color palette, adding a layer of fantasy to the everyday workings of commerce. Indeed, the majesty of the tall mast, the red mountains, and the endless sky endows the scene with mythic qualities that Leighton otherwise bestows on more typical subjects of such treatment, such as nymphs, Greek gods, and Biblical figures, in his artistic oeuvre.

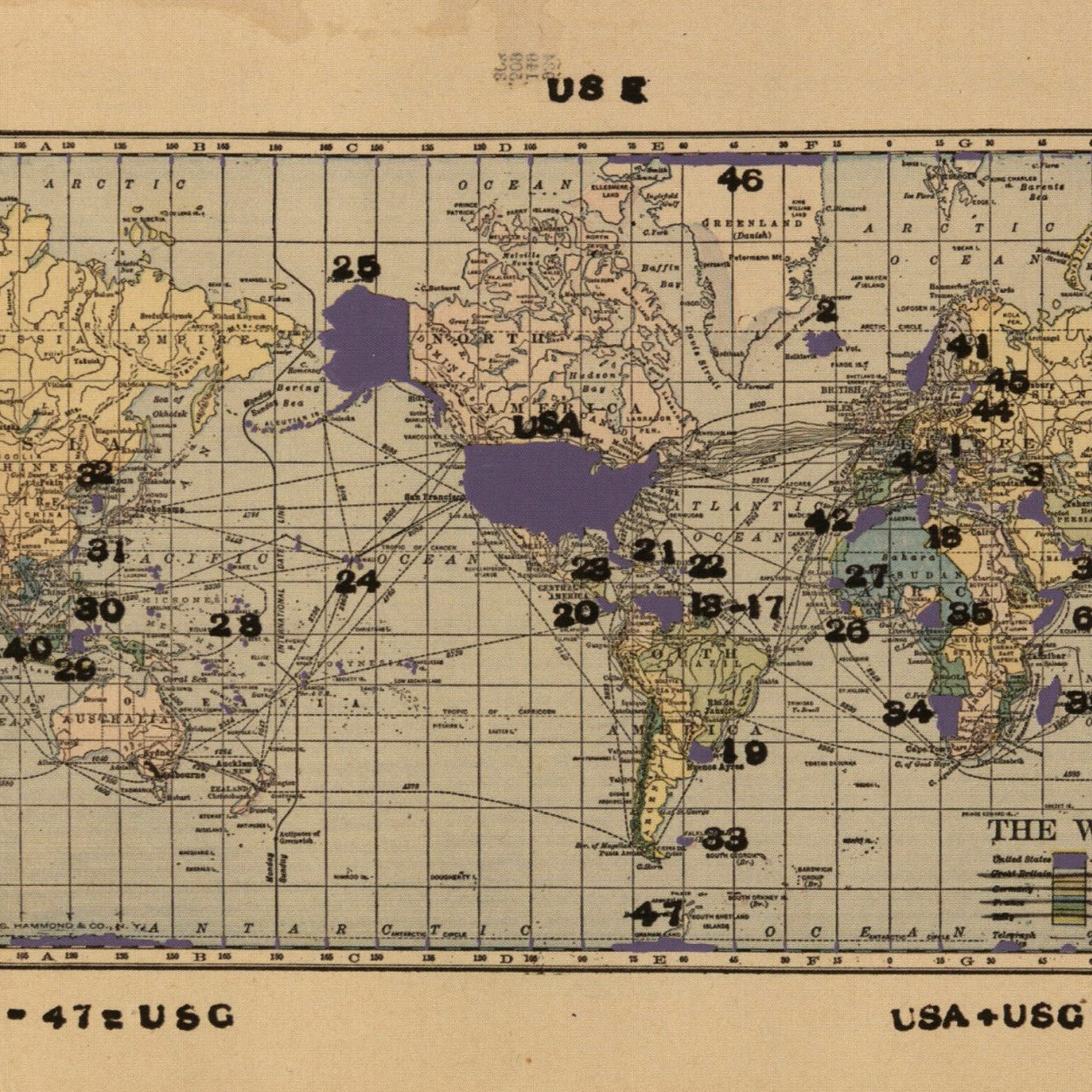

For Leighton’s viewers who had never traveled outside of Europe to see the Suez Canal or the East, this painting simultaneously granted them a keyhole view into this distant scene while speaking to them in the familiar language of Oriental fantasy. Such artistic representations of the East worked alongside other ways of knowing a place—such as maps, archeological findings, expeditions, and travelogues—to manufacture an understanding, both “objective” and fantastical, of the Orient that catered to the West’s scientific, commercial, and political interests. Together, these powerful representations both informed the direction that museums took in building their collections and, inextricably, encouraged the expansion of colonial empires.

Written by Daniel Pfeiffer

![Howard Russell Butler's [Hydrogen prominences]](https://futureoftruth.media.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2921/2023/01/k6584-square.jpg)