Roy Chapman Andrew’s Canteen

Circa 1928 (this pattern was patented in 1918 by Sigmund Frey, and is probably US Government surplus from WWI)

8” diameter, strap 41” Long

Bear Brand, Woolwine Metal Products Company, Los Angeles, CA

Aluminum or galvanized steel. Cork and cotton canvas

Stencil on front of canteen reads “GOVERNMENT;” initials “RCA” at center of back

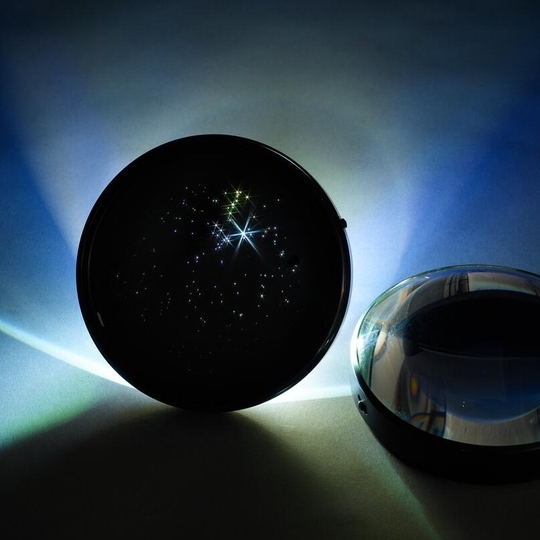

Research expeditions were an occasion to deploy new technologies. Many of the objects presented in the Seeing Truth exhibition represent new products and technologies used and sometimes conceived for use in seeking and producing knowledge. Pictured above is a flashlight and canteen from the 1928 leg of the Central Asiatic Expedition. Why are such objects included in museum archival collections? Originally, the fossilized findings of the expedition were our focus. Today, however, , even the tools used on such research expeditions are objects of study and interest and tell us a great deal about what experiences and ideas informed the people involved in the expedition. The Central Asiatic Expeditions featured many “firsts” including the first use of automobiles in the Gobi Desert, the first “moving pictures” captured in the Gobi (see footage here), and, of course, dozens of newly discovered firsts of fossilized dinosaurs and mammals.

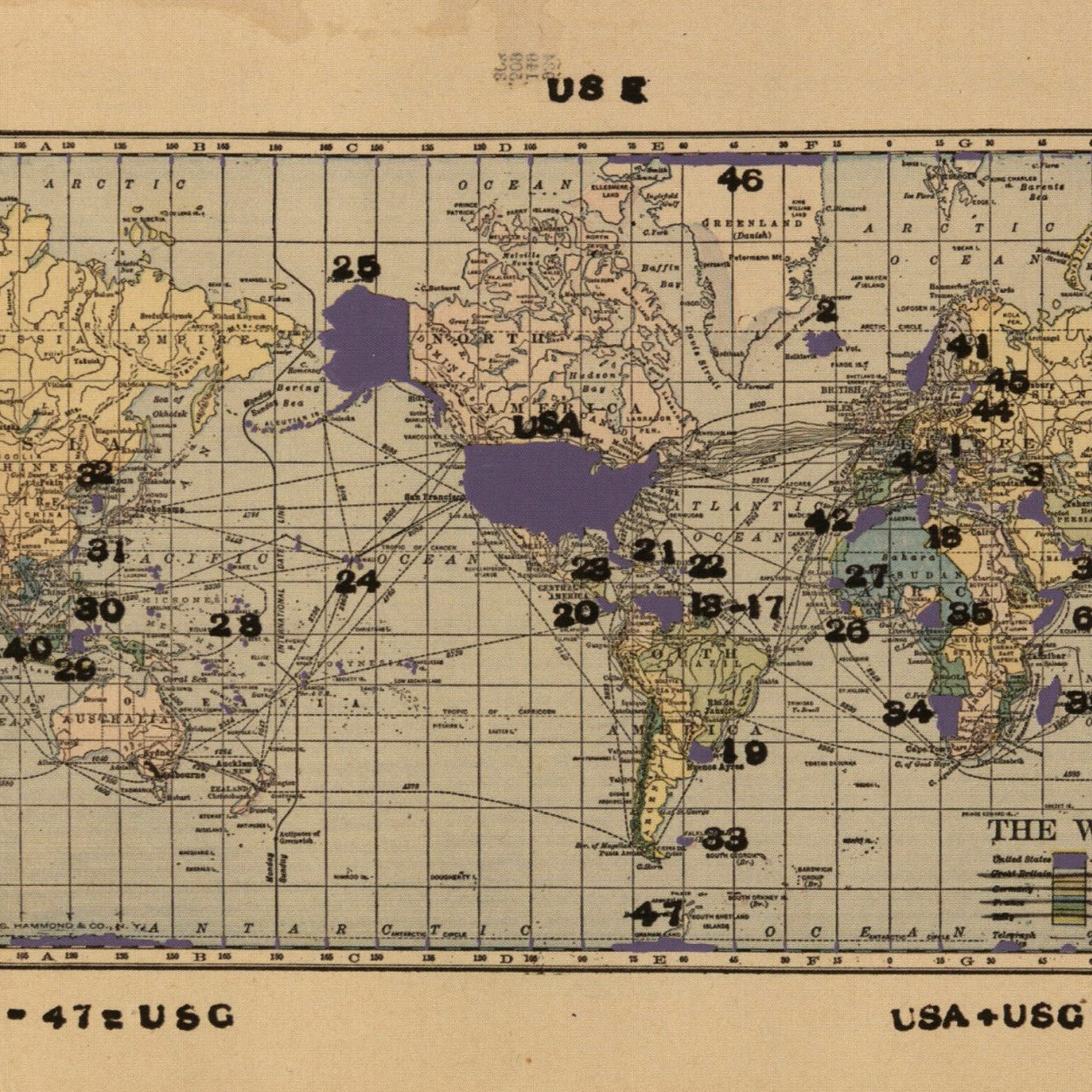

AMNH research teams dispatched to Mongolia and China included Roy Chapman Andrews, paleontologists, and a large support staff comprised of locals, often missionaries. The teams required motor vehicles, camels, camping supplies, and technical tools and supplies to unearth and carefully preserve fossils for transportation. Andrews made several trips to Mongolia and China leading up to the first official expedition. The expeditions of the 1920s were organized piecemeal, because Andrews and the AMNH often had to return home to the US in order to process their findings and raise funds. Maps had to be drawn and local guides, suppliers, camels, and governments had to be contracted. Planned excursions were also often paused due to civil war and unrest in China and Mongolia, and efforts were eventually halted in 1930 when the Mongolian government came under Soviet influence and subsequently closed its borders to Westerners.

Dr. Jose Perez, owner of the flashlight, served as the surgeon for the 1928 Expedition. He operated on Andrews’ leg after an accidental self-inflicted gunshot wound and treated G. Horvath, assistant auto mechanic, for a knife injury.

We may wonder how Americans found themselves digging in the Gobi Desert and how it came to be that many of their discoveries found new homes on US soil. New generations of scientists and critical citizens have identified this practice as looting. The AMNH continues its research in the Gobi Desert today, but original specimens are no longer housed in the US. Once the fossil is uncovered, it is processed and replicated with plaster or lent to the Museum for preparation and study and then, the museum returns the specimen to local authorities and scientists in Mongolia. In this way, knowledge is still expanded, but with more sensitivity to the people on whose land items are found.

Written by Katrina Kish and Joel Sweimler

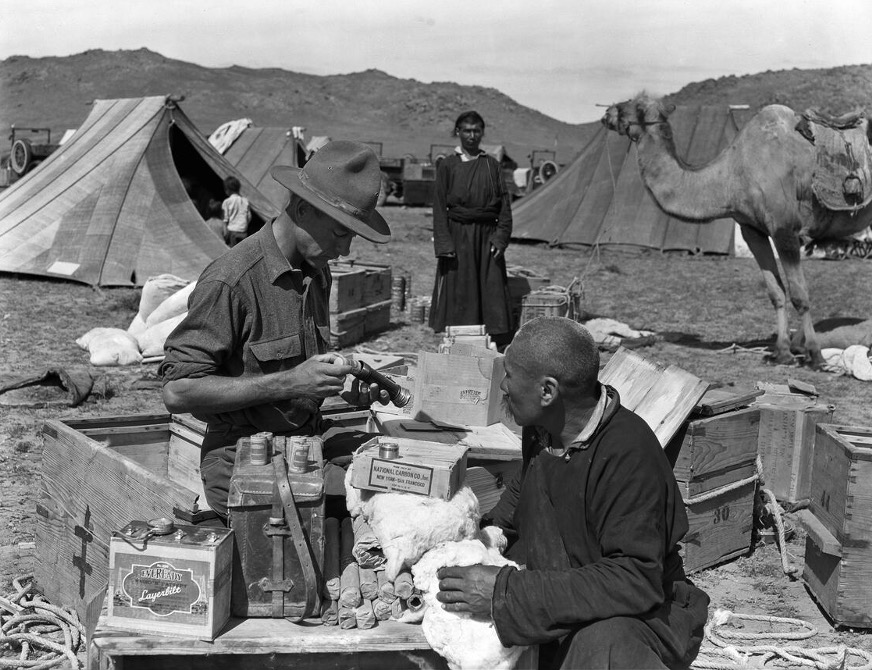

Roy Chapman Andrews refilling the flashlights with batteries. Mongolia, 1928.

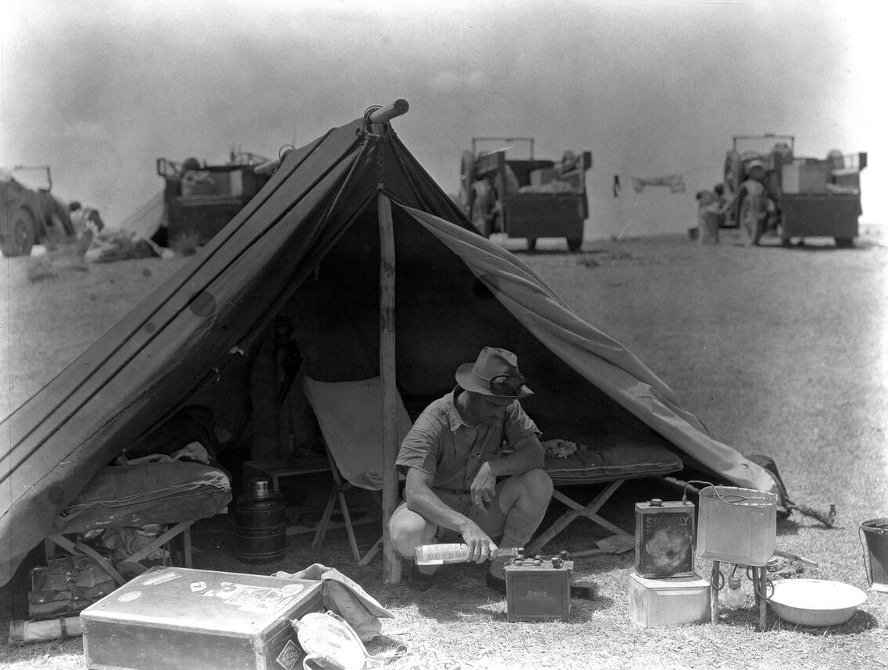

J. McKenzie Young, in charge of motor transport, distilling water for the radio and motor car batteries, Mongolia, 1928. A similar canteen can be seen lying against the box to the left of him.

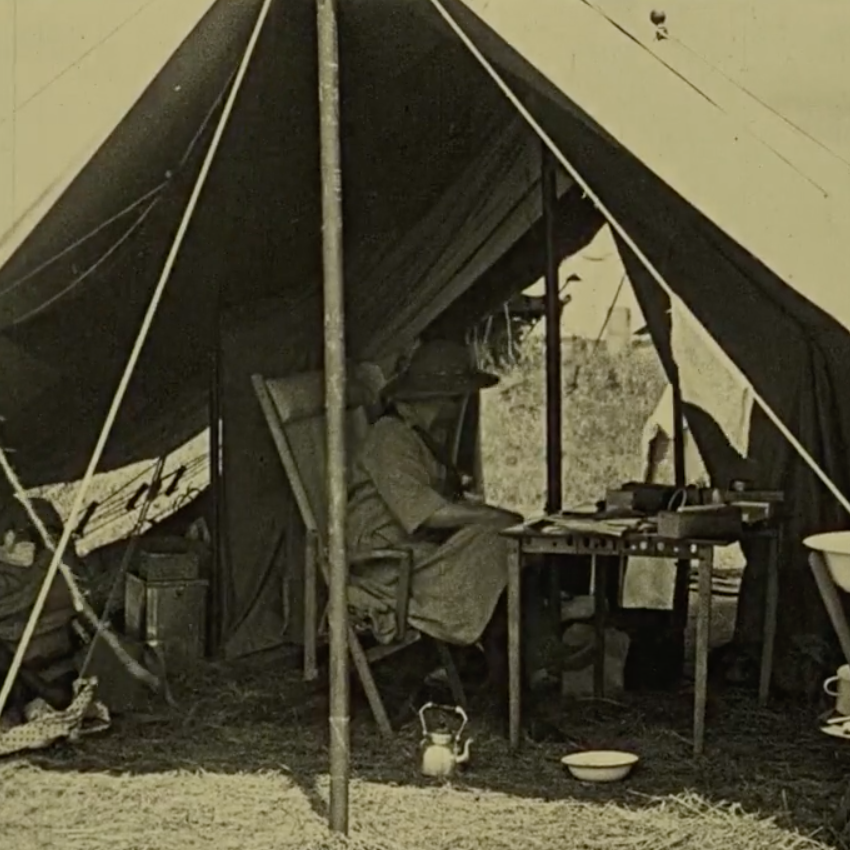

Expedition members listening to the Victrola at camp in the Gobi Desert. Andrews in front of the center tent pole and Perez is far right with a pipe. Mongolia, 1928.

![Howard Russell Butler's [Hydrogen prominences]](https://futureoftruth.media.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2921/2023/01/k6584-square.jpg)