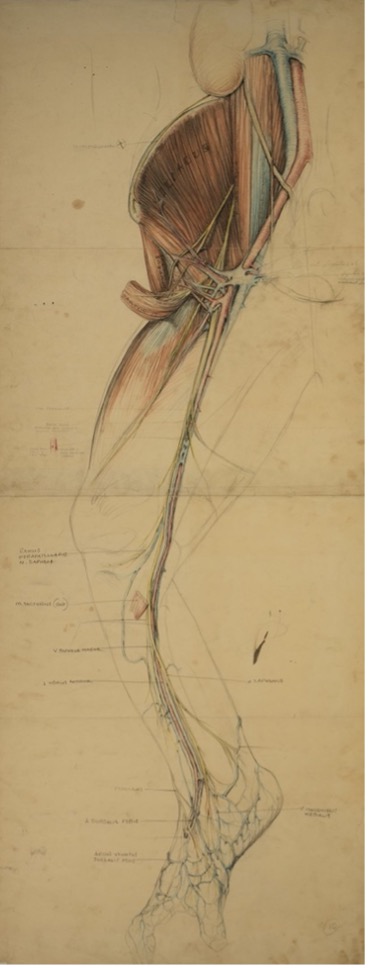

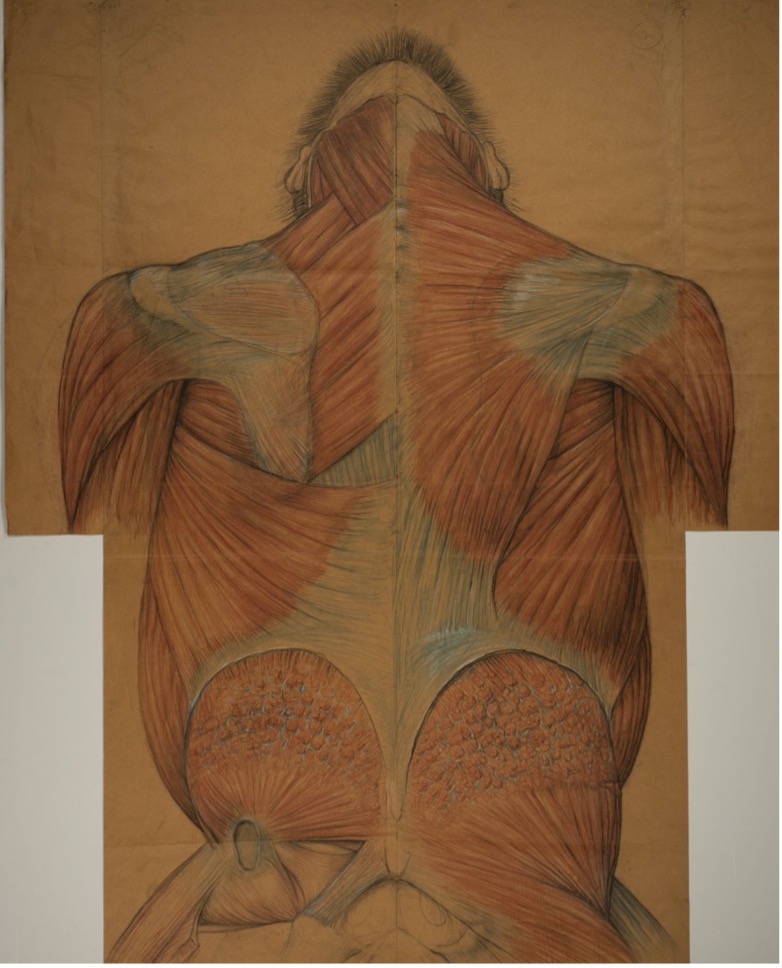

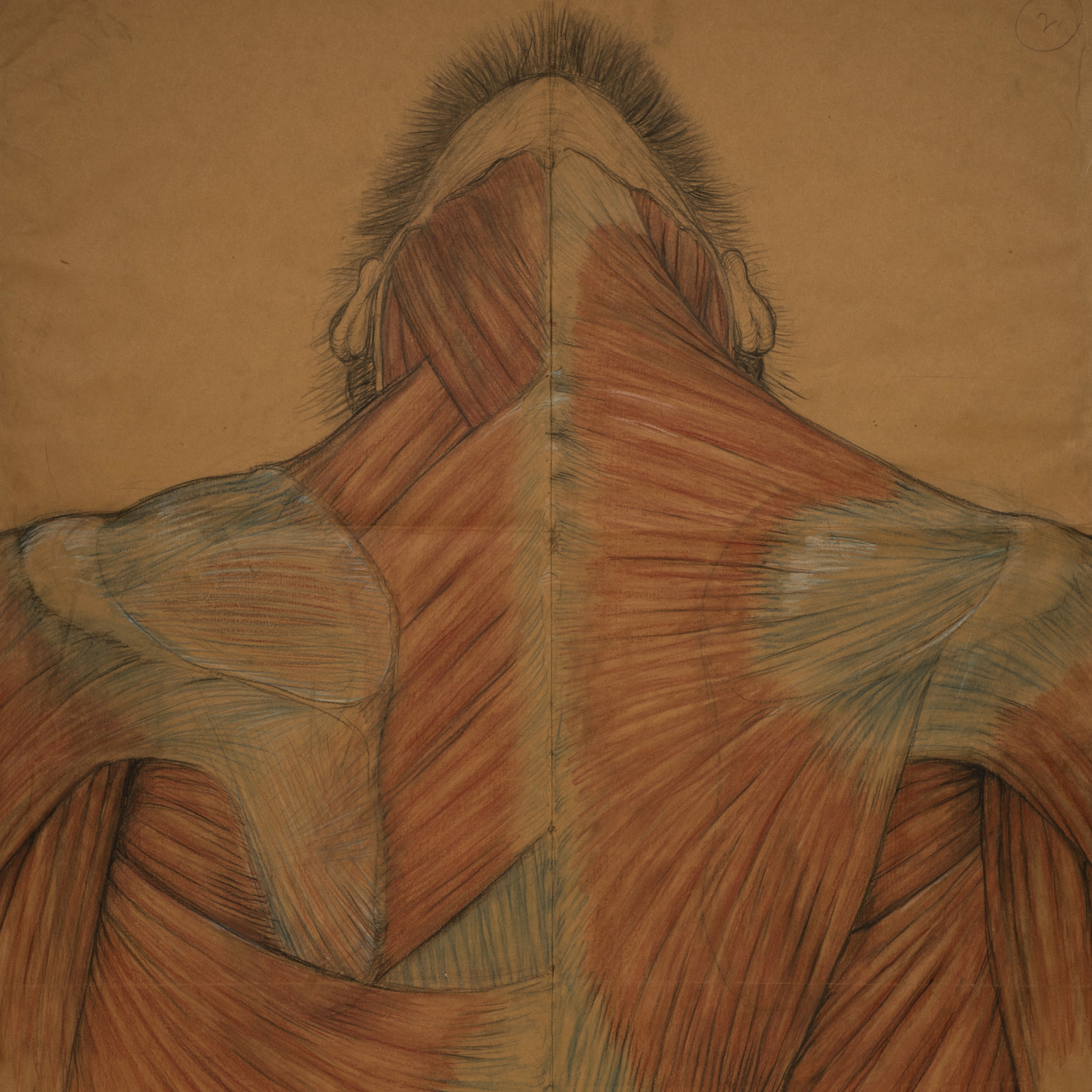

Right thigh and leg: Medial aspect, blood supply and nerves

1937-1943

32 ¼ x 43 2/3 inches

Betsy Garret [Bang], (1912-2003); Jeanet Steckler [Dreskin] (1921–)

Graphite and colored pencil on brown paper

Various inscriptions

46 ½ x 18 inches

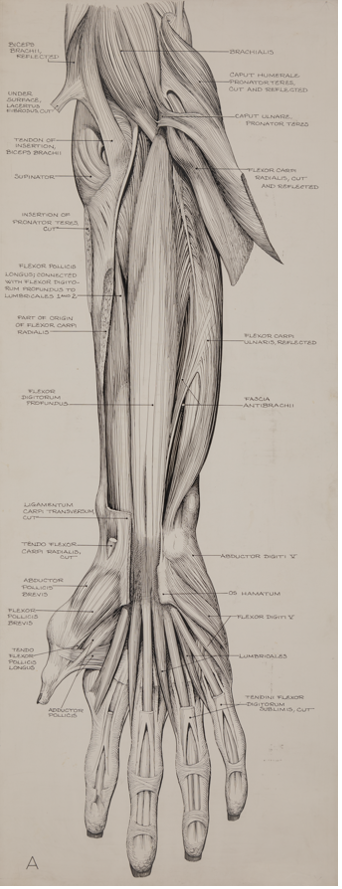

Right Forearm and Hand: Volar Aspect with Flexors

Ca. 1938

11x 28 inches

Betsy Garret [Bang], (1912-2003)

Ink on paper

Various inscriptions

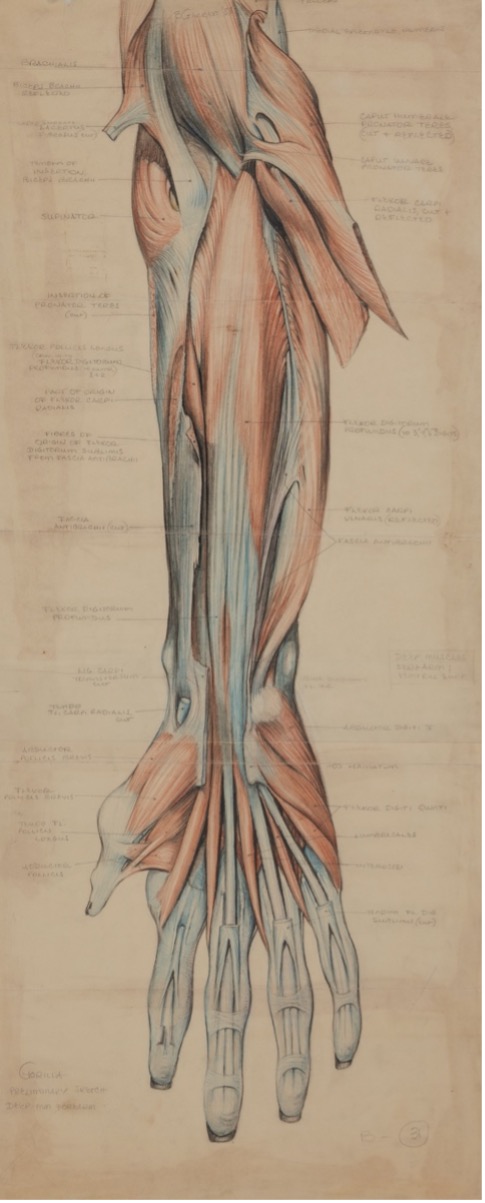

Right Forearm and Hand: Volar Aspect with Flexors

1938

12 x 29 1/8 inches

Betsy Garret [Bang], (1912-2003)

Colored Pencil on paper

Signed and dated “B. Garret 38” - Middle Top

various inscriptions – On reverse – “6/17/38/Natural Size/Drawn By/Orthometric Projection Natural” Size; “LL Front Gorilla/ Preliminary Sketch/Deep MM Forearm”

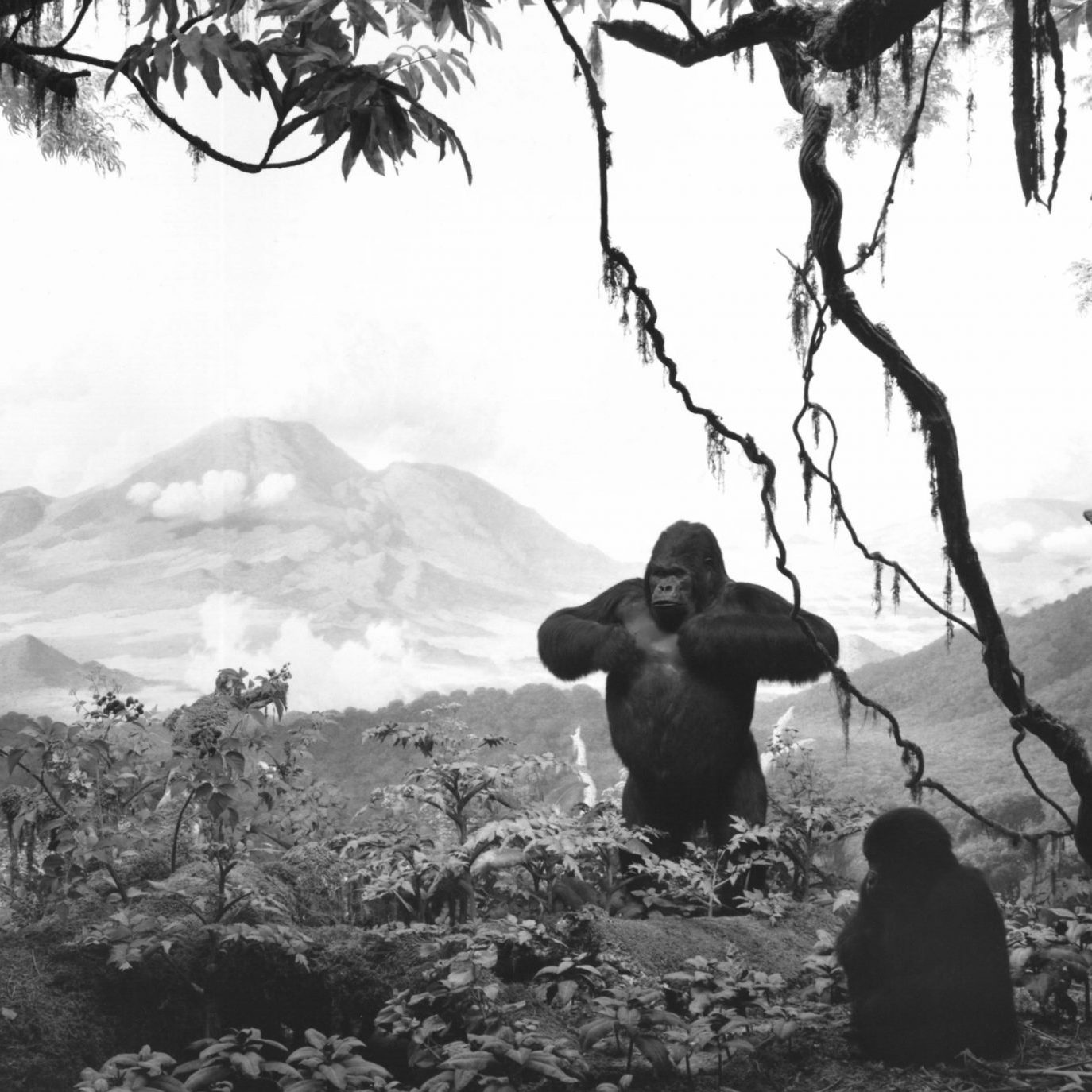

“The study of this ape [the gorilla] is perhaps more interesting and more important than the study of any other African beast that has been the center of so many fables and superstitions.”

Carl Akeley 1921

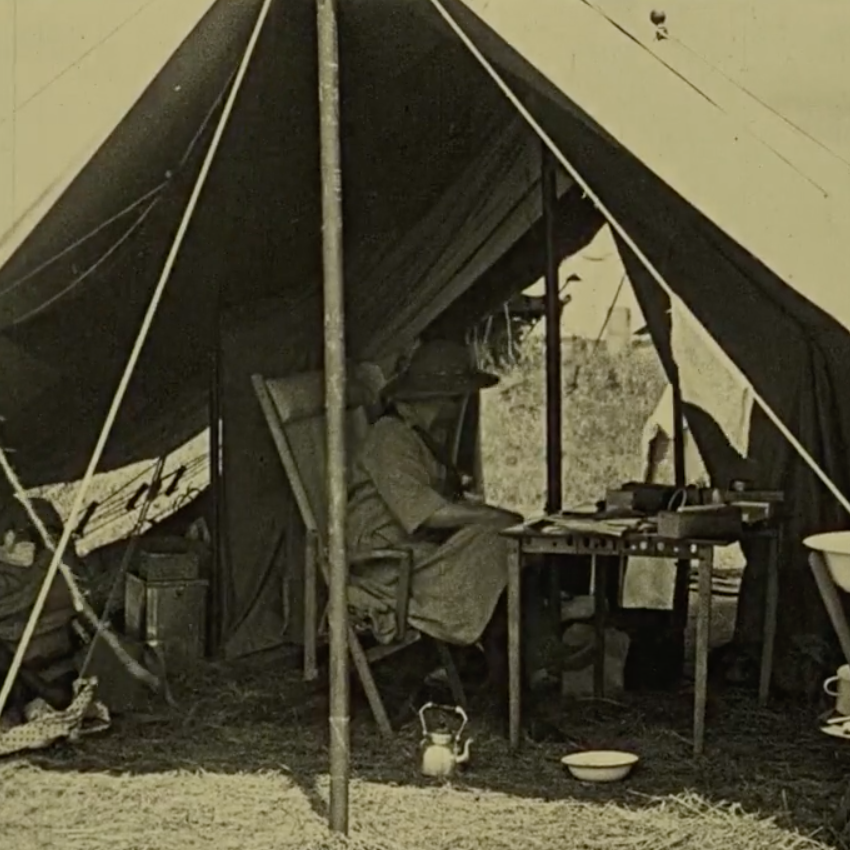

Henry Cushier Raven (1889–1944) was an expert taxidermist, anatomical illustrator, specimen collector, and an AMNH Mammalogy Department Curator from 1926 to 1943 whose work has incalculably broadened the study of the natural world. Raven frequently led expeditions to remote parts of the world for various institutions, including the American Museum of Natural History, to collect specimens and study organisms within their natural habitats. In 1929, the AMNH partnered with Columbia University to sponsor an expedition to examine gorilla behavior and bring back specimens of gorillas for anatomical study.

In 1936, Raven started working 3 to 4 months every year as an Associate in Anatomy and Prosector at the John Hopkins School of Medicine. While there he met and hired two students, Betsy Garret [Bang] and Jeanet Steckler [Dreskin] in the medical illustration program, taught by Max Broedel, the world-renowned medical illustrator and instructor who is credited with bringing “art to medicine”.

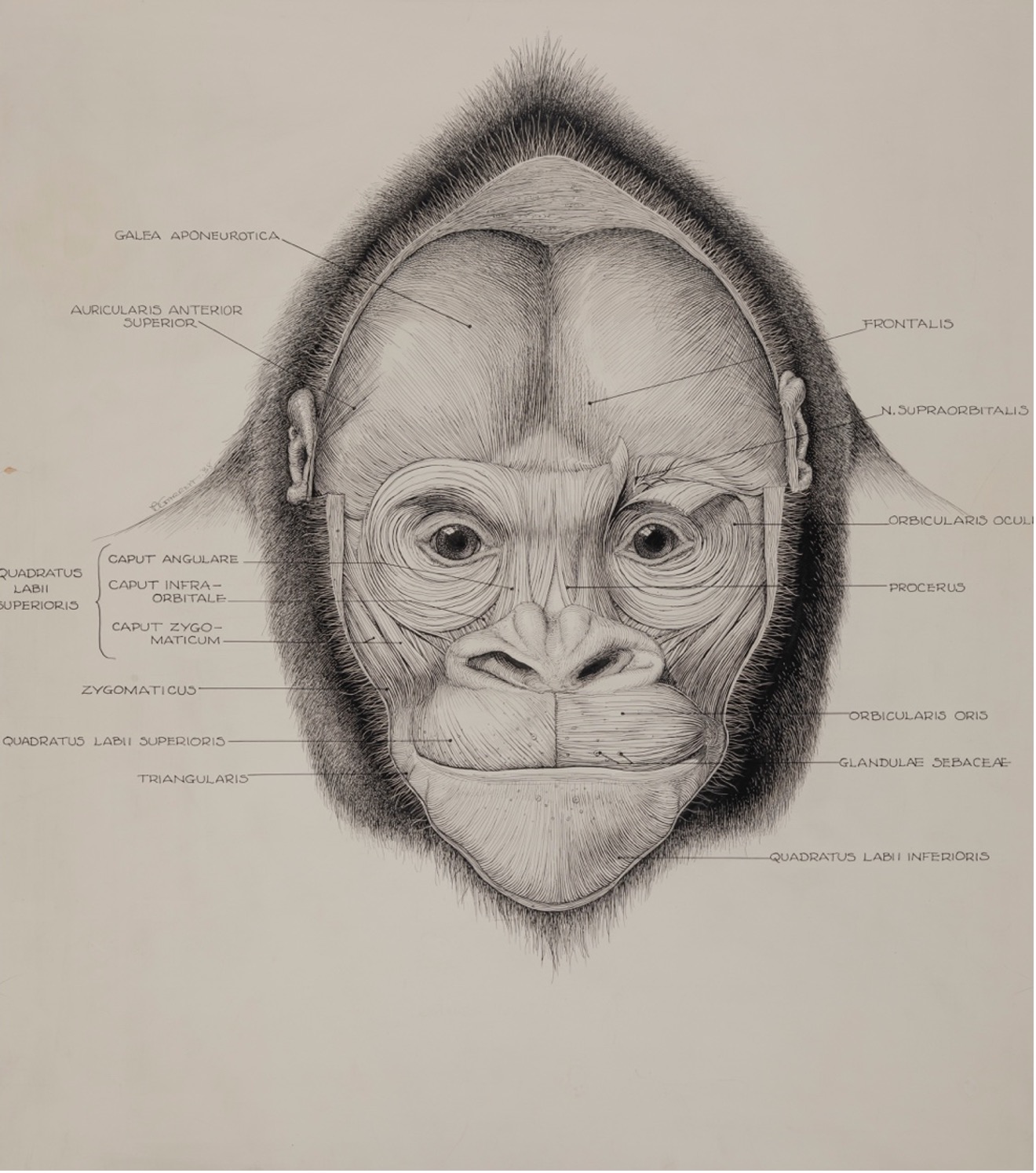

These life-size anatomical drawings of gorilla anatomy, made under Raven's close supervision by Garrett and Steckler, served as a key resource in scientific and medical education, particularly before the proliferation of medical imaging technologies. They reveal not only the anatomical structures of animals but also the relationships between different parts of their bodies. These detailed, hand-drawn illustrations of animal dissections provocatively show a visual tension between the efficiency of medical knowledge and the intrigues of artistic excess.

The illustrations included intricate life-size renderings of muscles and blood vessels, which Garrett preferred to draw between 1 a.m. and 5 a.m.—when the subways that shook the museum building ran less frequently. Steckler also found working in the Museum distracting and requested—and was granted—permission to work on the drawings at home.

Garret worked on the project until 1940 when she moved back to Baltimore and married Dr. Frederik Bang, whom she met when he wandered into her dissection lab at John Hopkins and enquired what she was doing with the 700-hundred-pound gorilla lying on the table. Raven died in 1944, from complications of malaria contracted on an expedition to Borneo in 1912, before the work was completed. Dreskin continued working on the project until 1946. The monumental volume on the anatomy of Gorillas was finally published in 1950 with Raven’s original text and contributions from other scientists.

Dreskin later moved to the Midwest where she worked as a medical illustrator at the University of Chicago and then moved to Greenville, SC where she still works as a fine artist at the age of 101. Garrett continued working on scientific illustrations, co-authoring several articles with her husband as well as translating and illustrating a volume of folk tales of India. She is also known for her discoveries of the olfactory systems in many birds, which proved they had a sense of smell.

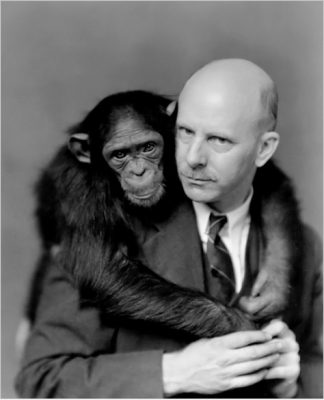

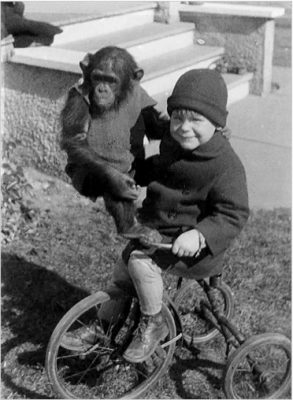

Outside of the scientific field, Raven is best known for his unofficial adoption of Meshie, a small orphaned infant chimpanzee he purchased while exploring the Congo in 1929. Meshie, who was popular with the local media, lived with Raven’s family in Baldwin, Long Island for 5 years, living and interacting with Raven’s young family. In 1932, he produced a movie of his family and their life living with Meshie. Meshie, child of a chimpanzee. 1932.

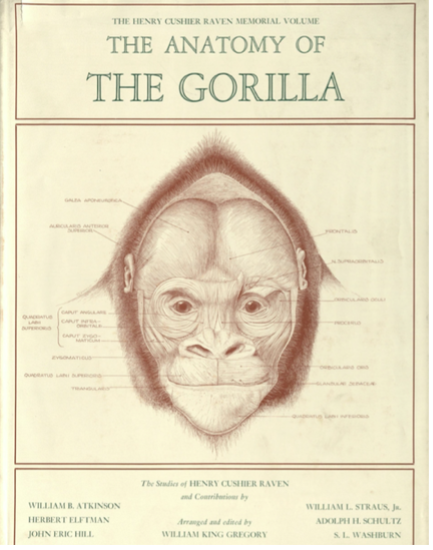

Cover from The anatomy of the gorilla

Or, "The studies of Henry Cushier Raven, and contributions by William B. Atkinson, Herbert Elftman, John Eric Hill, Adolph H. Schultz, William L. Straus, Jr., S.L. Washburn; Arranged and edited by William King Gregory"

New York, Columbia University Press, 1950

A collaborative work of the American Museum of Natural History and Columbia University.

Harry Raven, Henry Raven’s oldest son, with Meshie in 1932. As an adult, Harry authored a book about growing up with Meshie. He writes that it was not all fun and games, “You never forget the rival who cast a shadow over your childhood, monopolizing your father’s love and attention, clearly preferred. This is especially true if she has bitten your hand so deeply that nearly 80 years later, a scar is still there.”

Harry Raven, Henry Raven’s oldest son, with Meshie in 1932. As an adult, Harry authored a book about growing up with Meshie. He writes that it was not all fun and games, “You never forget the rival who cast a shadow over your childhood, monopolizing your father’s love and attention, clearly preferred. This is especially true if she has bitten your hand so deeply that nearly 80 years later, a scar is still there.”

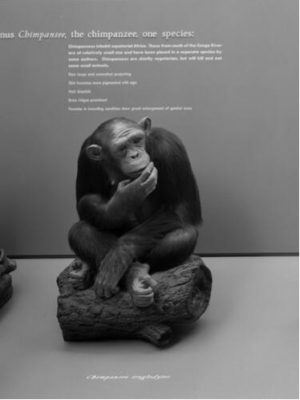

By 1934 Meshie, now seventy pounds and as strong as a man, had become unmanageable. She was brought to the Brookfield Zoo in Chicago where she died in 1937 after giving birth to a daughter. Her remains were returned to the AMNH for preparation and she presently can be seen in the Hall of Primates, sitting on a log, her chin propped up on her knuckles, looking pensively at all who pass.

Co-written by AMNH Staff and Daniel Pfeiffer

![Howard Russell Butler's [Hydrogen prominences]](https://futureoftruth.media.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2921/2023/01/k6584-square.jpg)