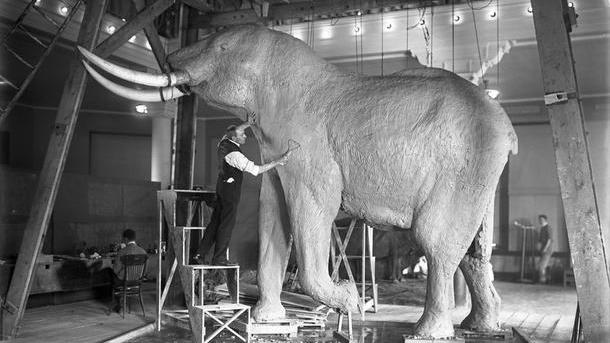

Akeley-Eastman-Pomeroy African Hall Expedition of the American Museum of Natural History (1926)

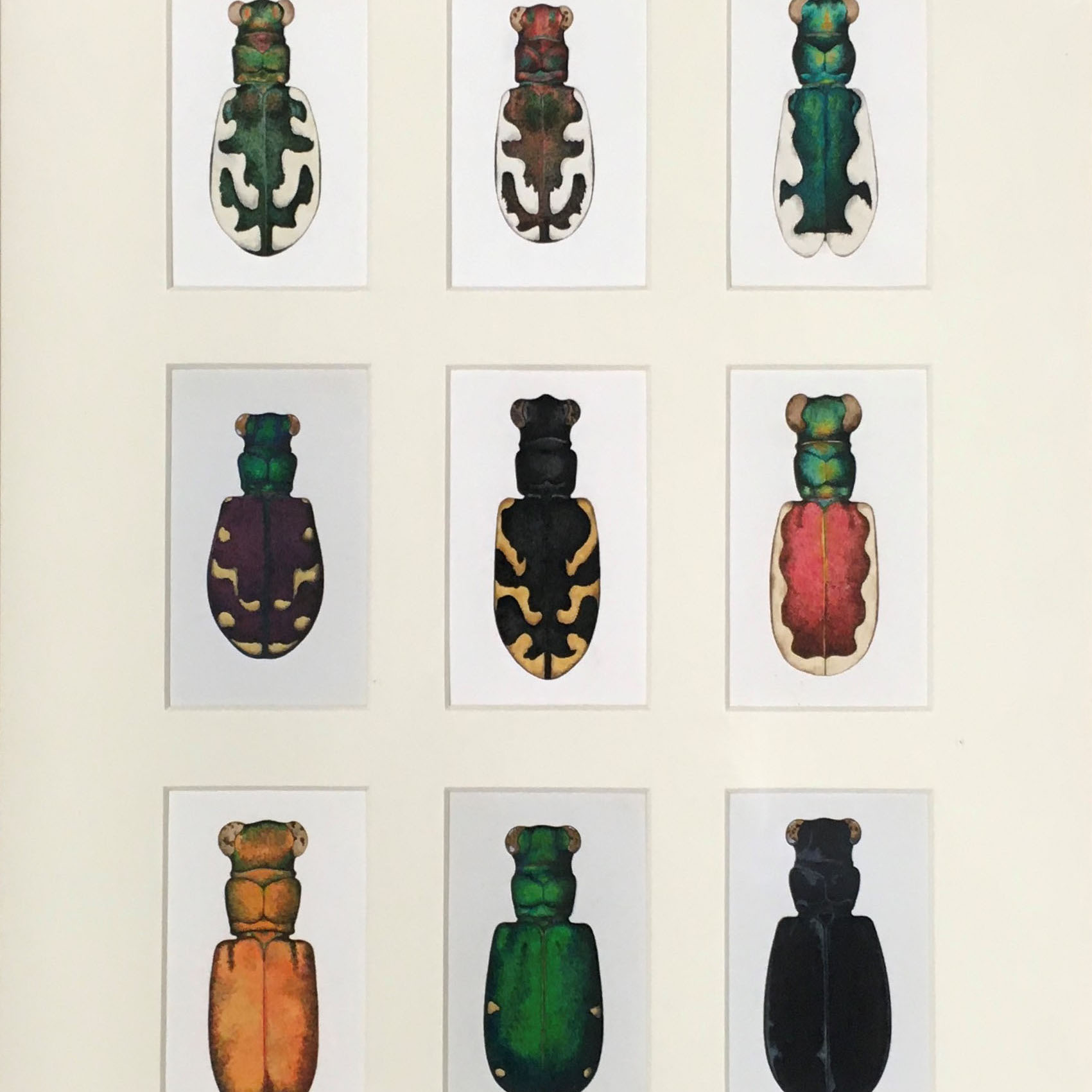

Conservationist Carl Akeley (1864–1926) contributed hundreds of specimens and images of wildlife and plants to various American museums throughout the course of his career, which took him from Wisconsin to Somaliland and the Congo. His original taxidermy techniques, known as the Akeley method, sought to preserve his specimens so that they looked not only real but alive within accurate recreations of their natural habitats. These innovations added a new level of realism to museum displays and earned him the title of the father of modern taxidermy.

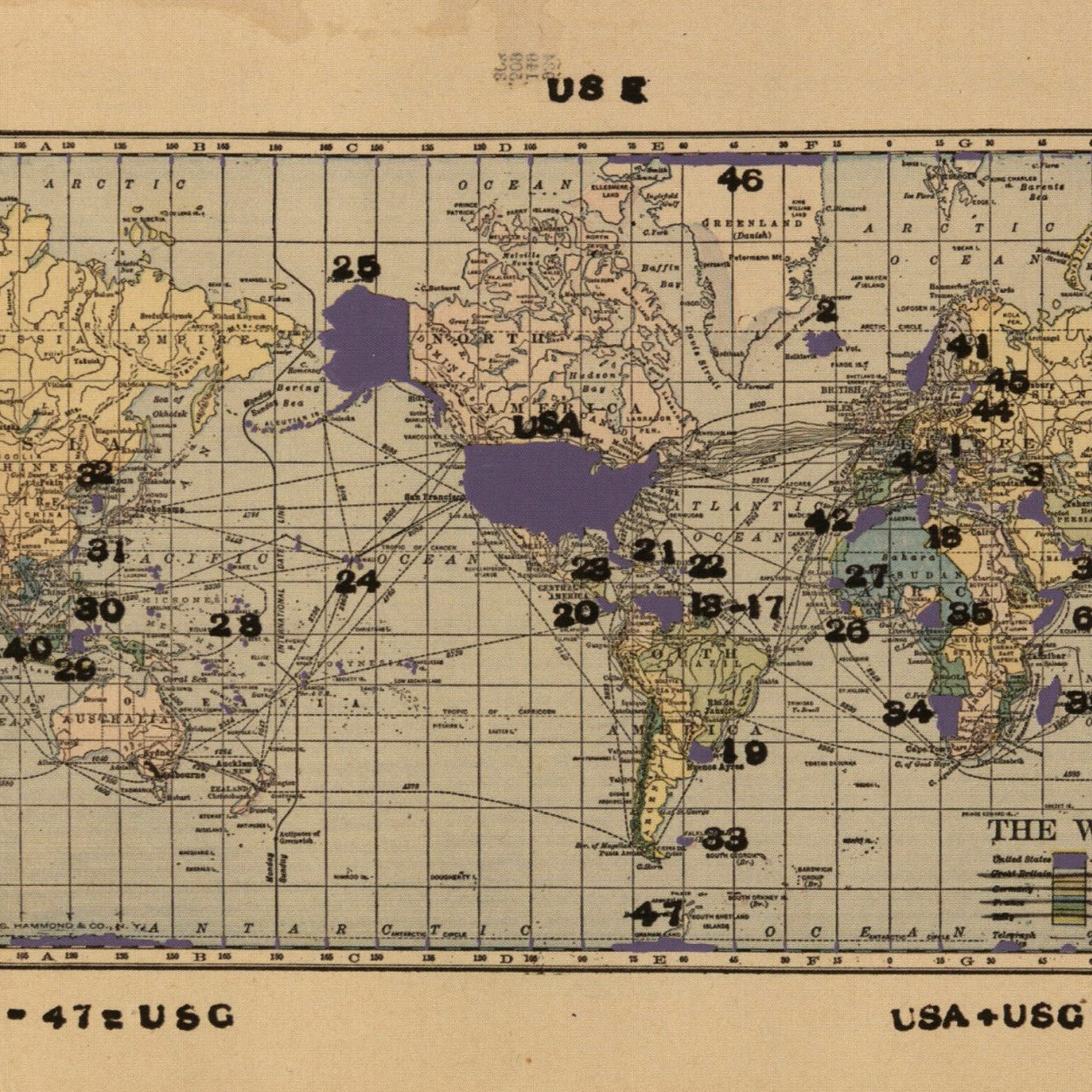

Carl was not alone in his specimen-hunting endeavors; both his first and second wives were accomplished explorers in their own right. His second wife, Mary Akeley (1878–1966), accompanied him on his final and her first expedition to Africa in 1926, captured in the above video. Although Carl would die of dysentery before the expedition concluded, Mary completed the expedition and contributed many specimens, photographs, and maps to the findings of the exploration team. She wrote several books about her travels that helped to popularize the knowledge that the team gained.

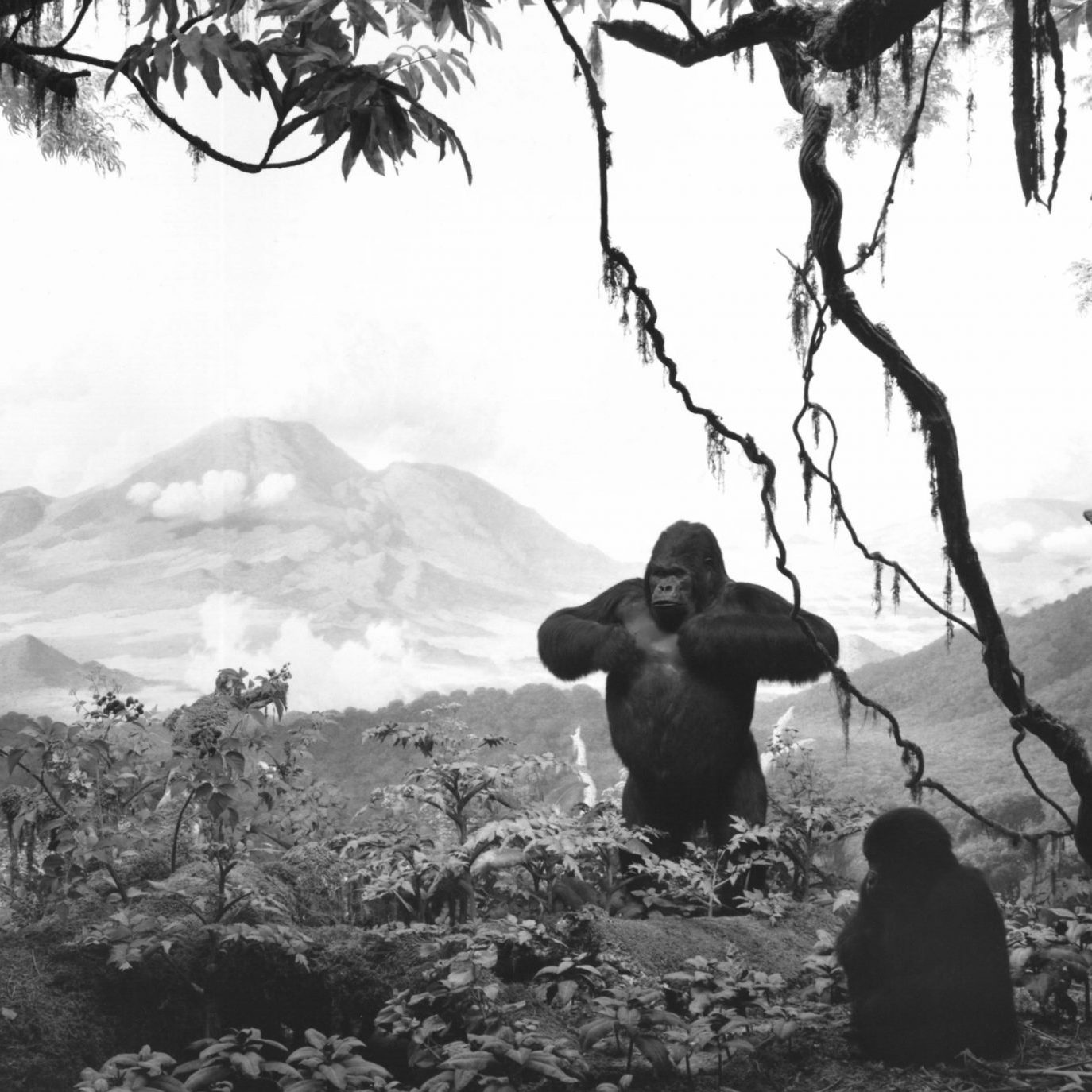

In honor of his contributions to the museum, the American Museum of Natural History named the Akeley Hall of African Mammals after Carl. The Hall’s centerpiece is a herd of lifelike, taxidermied elephants seemingly on the move, surrounded by dioramas—many of which feature specimens by Carl and Mary—that showcase other animals, including gorillas, lions, and ostriches.

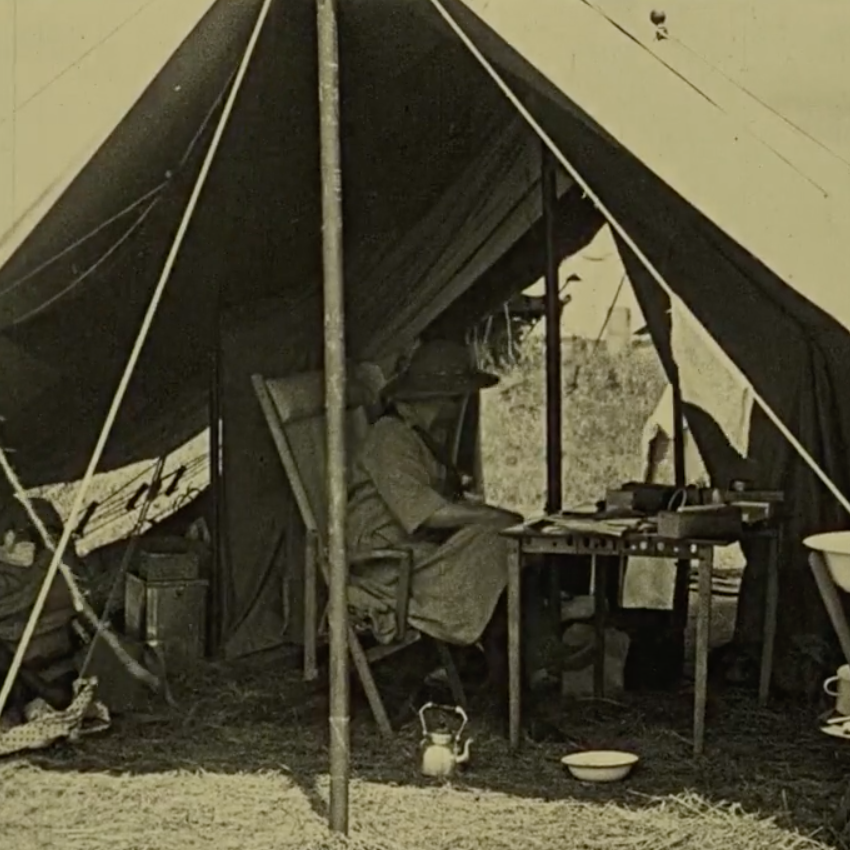

The film of the Akeleys’ 1926 expedition to Africa provides an insider view of what an expedition is like. Clearly evident in this recording is the industry involved in specimen-taking and researching. The film dispels the myth—steeped in American rugged individualism, of the explorer as a solitary white man, à la Indiana Jones—and shows the collaborative nature of the team’s scientific, artistic, and domestic work. The relationships between the researchers in the first half of the film are as complex as the relationships between animals and their habitats highlighted in the second. Indeed, Akeley’s own understanding of the natural world as a series of intricate interactions between wildlife and their environment, which his dioramas sought to capture, extends to the expedition's vision of knowledge production as a cooperative and social act.

Written by Daniel Pfeiffer

![Howard Russell Butler's [Hydrogen prominences]](https://futureoftruth.media.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2921/2023/01/k6584-square.jpg)