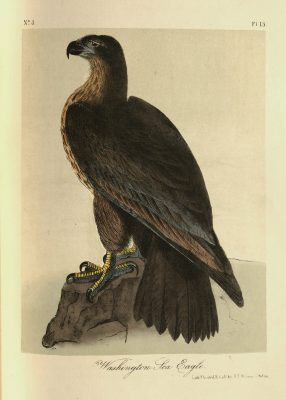

Bird of Washington from Ornithological Biography, or, An Account of the Habits of the Birds of the United States of America : Accompanied by Descriptions of the Objects Represented in the Work Entitled The Birds of America : and Interspersed with Delineations of American Scenery and Manners

Bird of Washington from Ornithological Biography, or, An Account of the Habits of the Birds of the United States of America : Accompanied by Descriptions of the Objects Represented in the Work Entitled The Birds of America : and Interspersed with Delineations of American Scenery and Manners

John James Audubon, William MacGillivray, and Adam Black

1831, Edinburgh

Edited by Adam Black, [and 8 others].

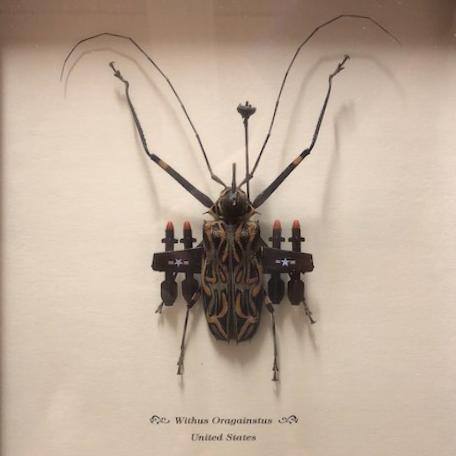

The National Audubon Society, the well-known environmental nonprofit organization and the American authority on birds, takes its name from John James Audubon (1785–1851), a painter and ornithologist who was determined to document and illustrate every species of American bird in their natural habitats. Audubon’s typical process involved first shooting each bird and then posing the specimen to imitate its natural character and highlight notable aspects of its body. Audubon collected and published the more than 400 illustrations he had made, along with descriptions, in The Birds of America between 1827 and 1838. This monumental work remains an important touchstone for ornithologists.

Pictured above, the Bird of Washington, or Washington Sea Eagle, is unique among the entries in Audubon’s study, because no one has confirmed its existence. Audubon claims to have discovered the bird near the Great Lakes in 1814 and reports seeing it multiple times. But he departed from his usual artistic method by not collecting a specimen of the Bird of America (although this claim is contested). Some of his friends and contemporaries anecdotally reported their own sightings, but there has been no hard proof of the bird’s existence.

For someone whose oeuvre and love of birds is relatively quite fastidious, Audubon’s inaccuracy here has perplexed scholars. Some suggest that Audubon fabricated it to inspire interest and some controversy in his book; others postulate that the bird may have gone extinct or that Audubon simply confused it with another type of eagle.

So what do we make of the Bird of Washington? This question points us to a level of uncertainty within the scientific record that is often ignored and hard to accept. But the natural world, in spite of scholarly attempts to pin it down and catalogue it, eludes scientists as often as it reveals its truth to them. The uncertainty of this bird’s existence recalls the ongoing replication crisis in many natural and social science fields. Scholars have shown that the results of many fundamental scientific studies cannot be reproduced, calling into question the accuracy of many findings as well as the decisions made using those studies. Such instances of ambiguity remind us that science, despite its purported drive toward identifying, knowing, and cataloguing, is always the domain of uncertainty.

Written by Daniel Pfeiffer with assistance from Kristin Eshelman

![Howard Russell Butler's [Hydrogen prominences]](https://futureoftruth.media.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2921/2023/01/k6584-square.jpg)