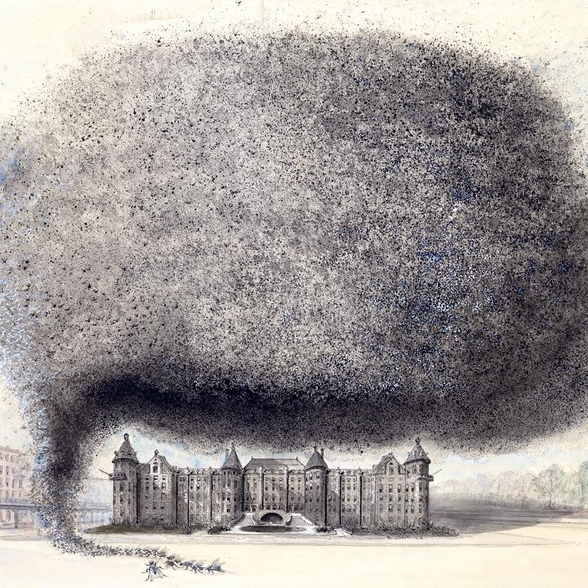

1914

16 ½ x 20 ½"

Albert L. Operti, 1852-1927.

Ink and watercolor on paper

Inscription on reverse in pencil "Dr. Lucas."

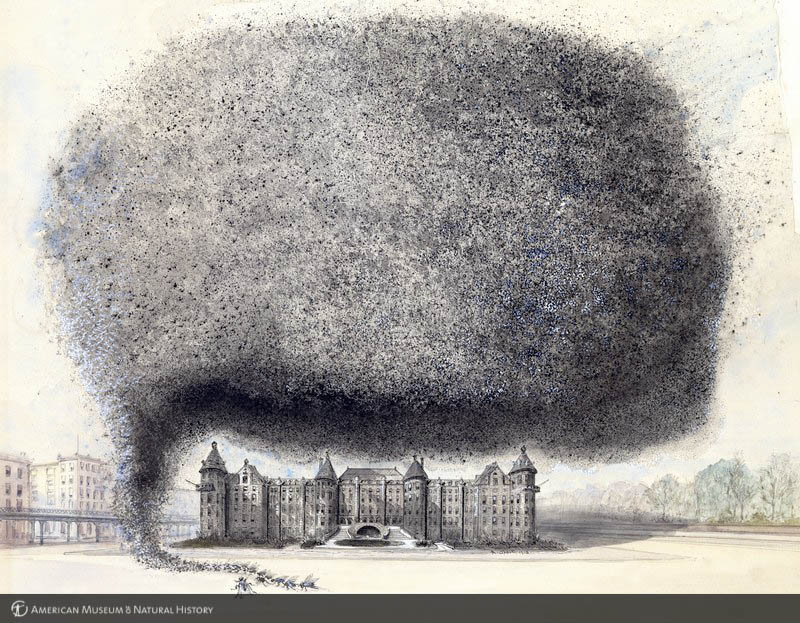

A humorous drawing depicting a huge swarm of flies over the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), after taking off in front of the south facade of the Museum. The Columbus Avenue elevated train track is shown on the left. While artistically inventive, the topic was deadly serious, meant to drive home the point of the damage that could be done in one generation of flies, let alone the nine generations depicted.

Italian-born Albert Operti, was a versatile painter, illustrator, and sculptor and for much of his professional career, served as a scenic artist for the Metropolitan Opera House and later was one of the first professional artists to work full time at the AMNH. Operti served as the official artist for Robert E. Peary during his Arctic expeditions of 1896 and 1897, producing paintings, drawings and even plaster casts of the Inuit encountered on the expedition.

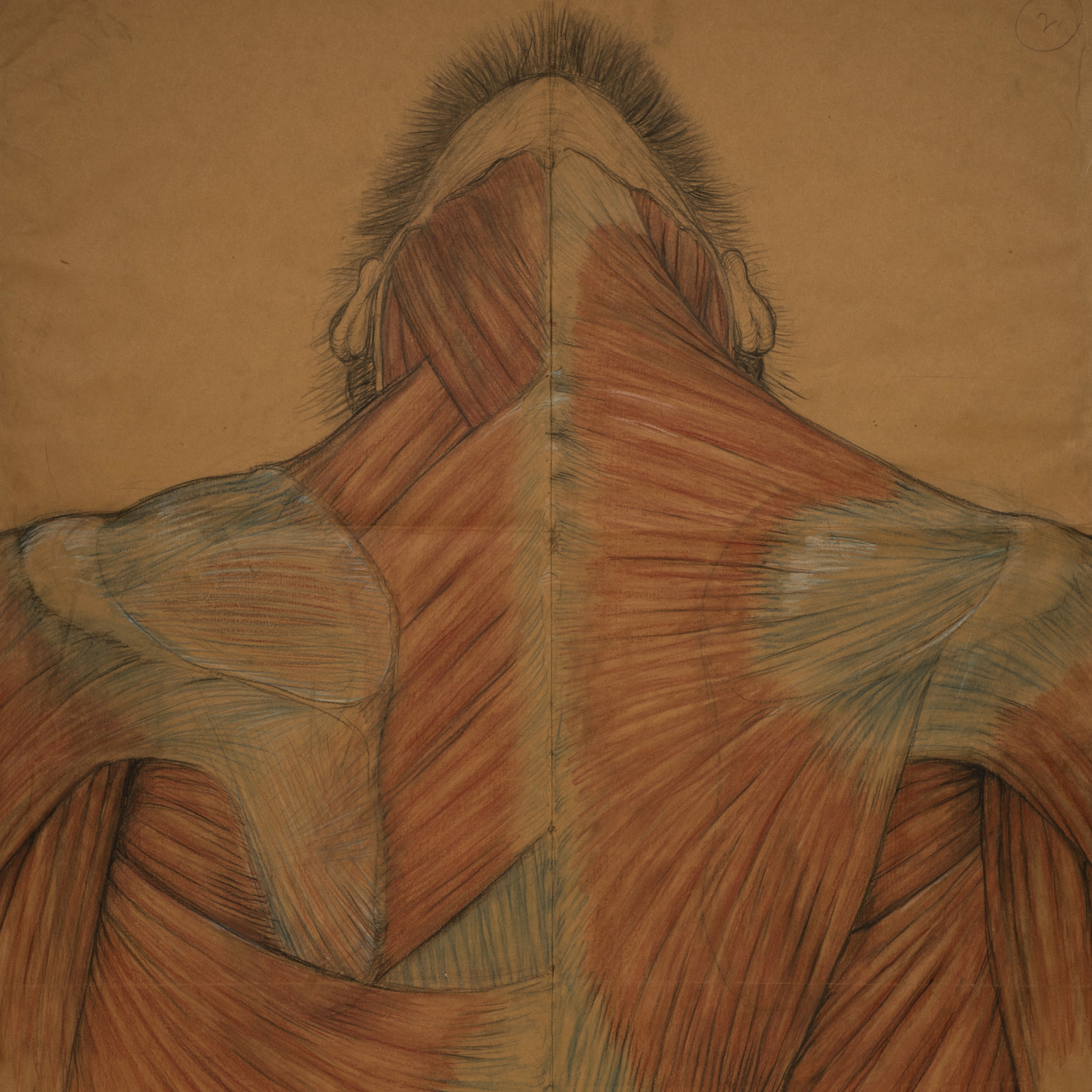

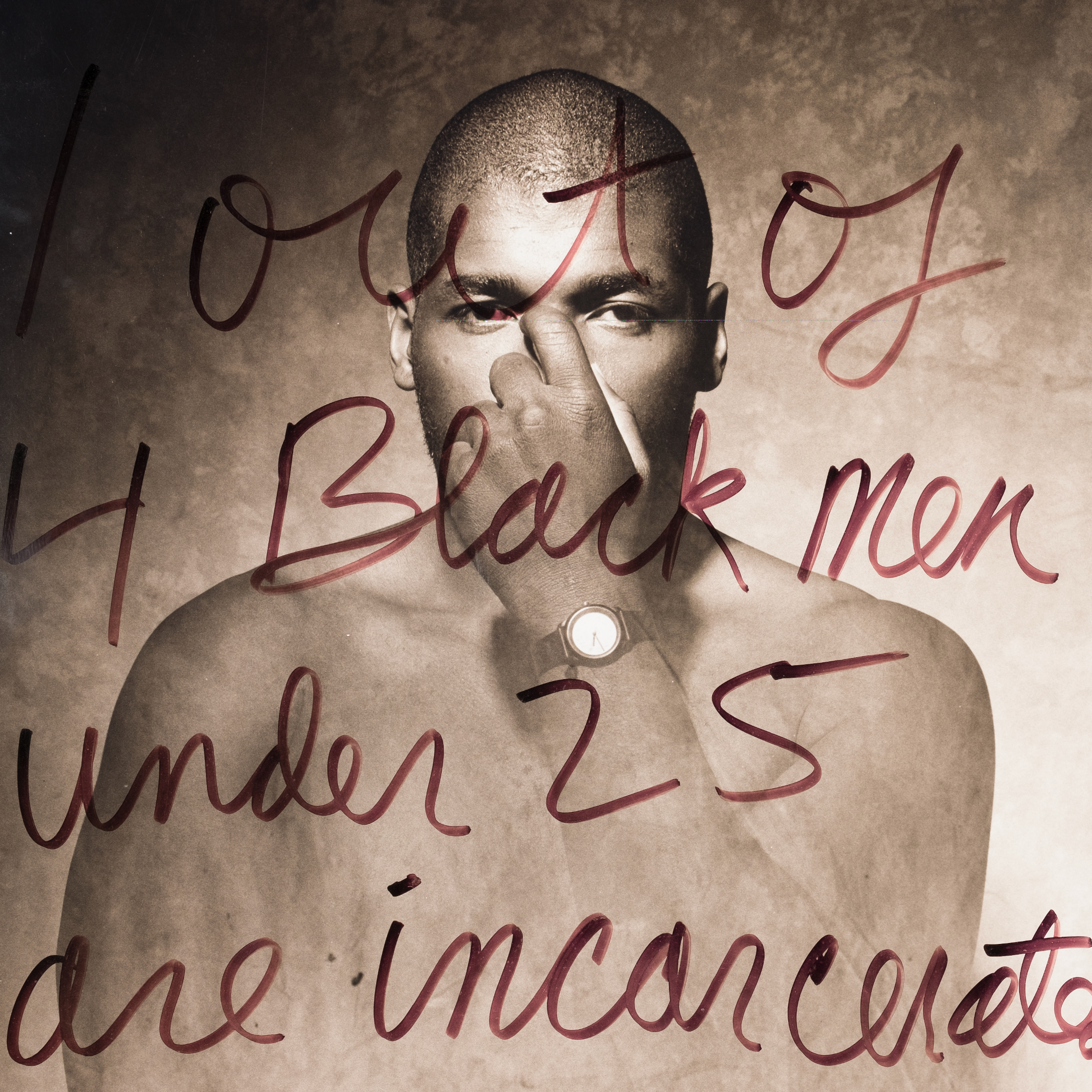

In 1909, curator Charles-Edward Winslow established a department of public health the AMNH. Winslow introduced public health as a biological science that connected human health—the modern sciences of physiology, hygiene, and urban sanitation—to the natural history of plants and animals. This was the only time an American museum created a curatorial department devoted to public health. The AMNH’s Department of Public Health comprised a unique collection of live bacterial cultures—a “Living Museum”—and an innovative plan for 15 exhibits on various aspects of health.

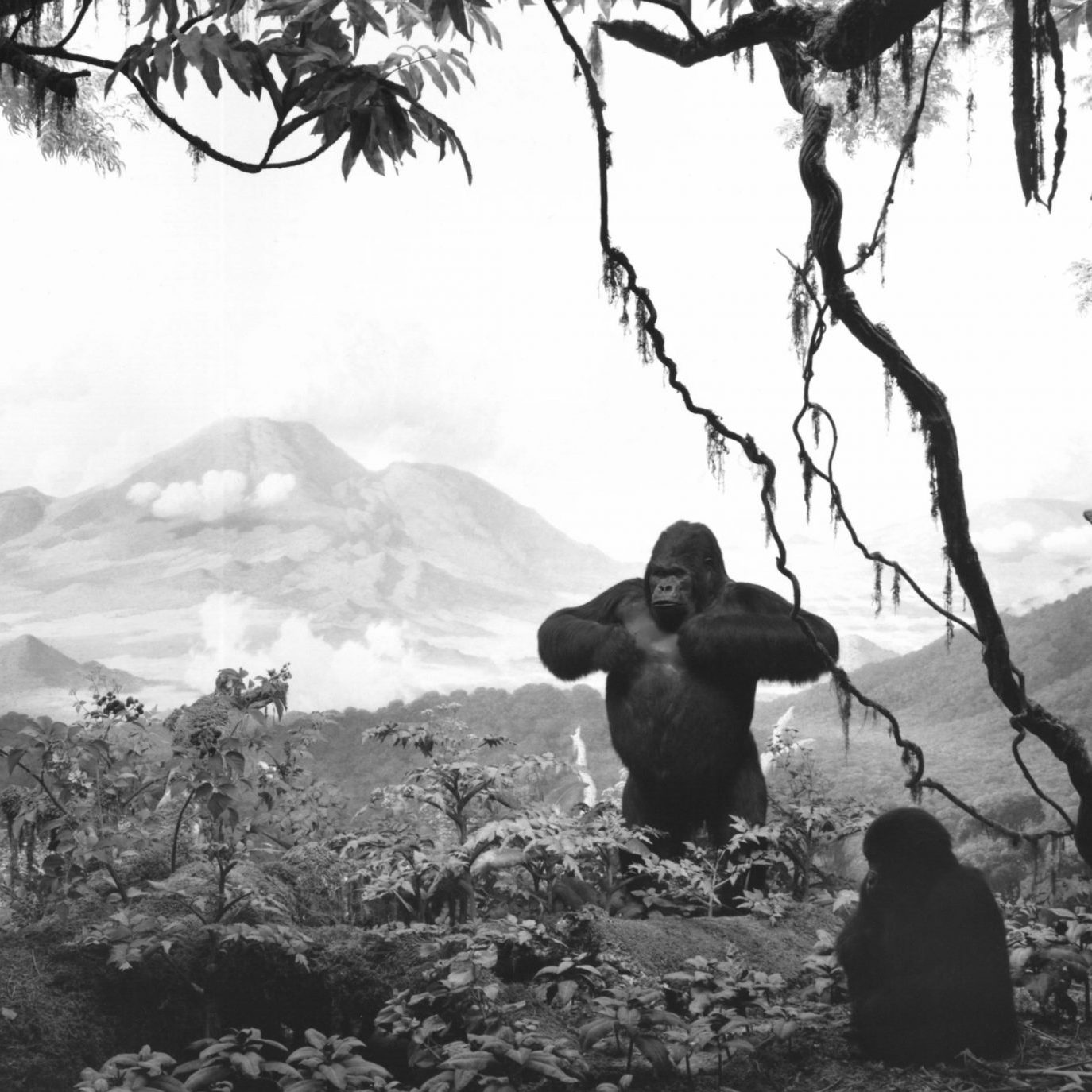

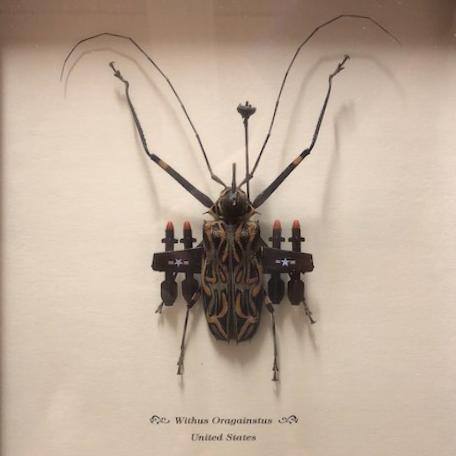

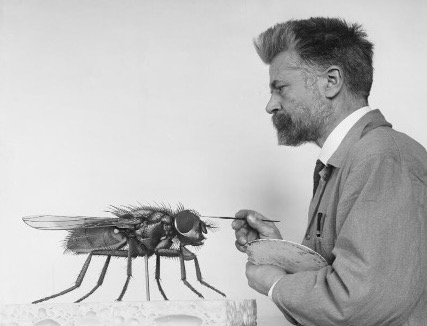

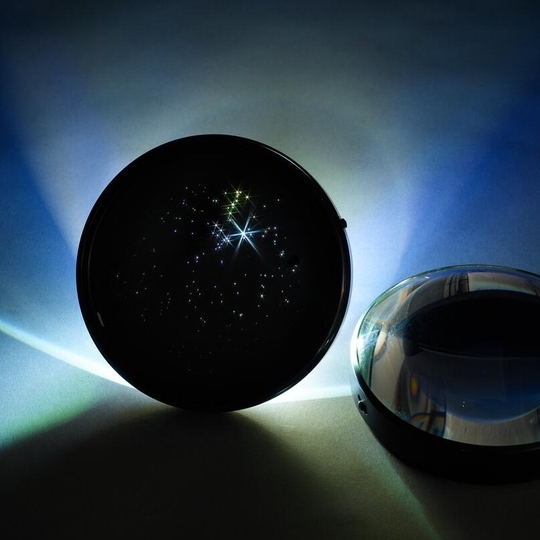

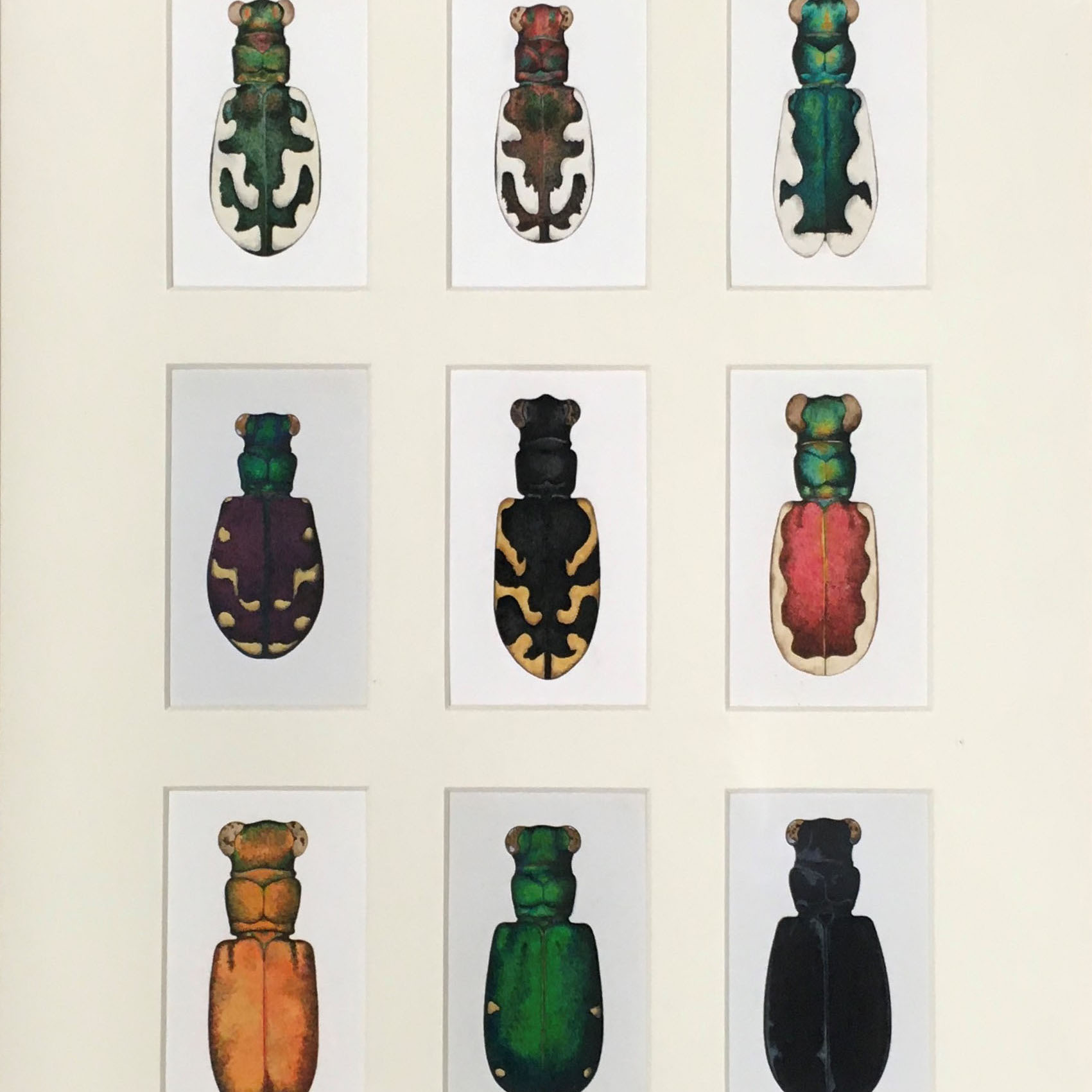

Artist Ignaz Matausch (right) was an Austrian-born artist and entomologist known for his models of insects and other invertebrates at the AMNH where he began working in 1904. He was known for his realistic large-scale models including the flea, house fly, and spider. The giant model “as big as a cat” of the common housefly (enlarged 40 times) used some 200 actual specimens as reference models, mostly living (chloroformed), to ensure the most accurate reproduction. Of course, the most difficult feature to reproduce was the compound eyes, each with 1,200 separate ocelli. It was the central feature in the exhibit on the most common disease-carrying insects at the April 1913 opening of the AMNH’s Hall of Public Health.

For over three decades, in various forms, the Museum’s Public Health Halls provided information on public health and sanitation to the burgeoning population of New York. This 1921 view of the Public Health Hall with a visiting group of students (below), shows the painting, visible in the case on the rear wall of the gallery and the fly model in the case on the right.

Ignaz Mattausch (1859-1915) working on a model of the common house fly or Filth Fly, Musca Domestica in 1913.

In the early 20th century, the AMNH hosted several health-related temporary exhibitions including two exhibits on tuberculosis (1905 and 1908), two on safety (1907 and 1908), and one on the “Congestion of Population” (1908), the first exhibition in the United States devoted to contemporary urban problems of overcrowded housing, inadequate school facilities, susceptibility to disease and illness, and lack of space for parks and recreation. It was the second Tuberculosis Exhibit (November 1908 to January 1909) that spurred the AMNH to establish a curatorial department for public health. Like other disease exhibitions of the period, it bombarded viewers with slogans, aphorisms, images, and a flashing-light display on death statistics—all pointing out the need for understanding, prevention, and treatment, and all filled with strong moral overtones. The exhibit was positive when it came to science: but it did underplay the uncertainties and failures of the new microbiology, the flaws and interpretive biases of public health surveillance and statistics, and the underlying social and economic causes of disease.

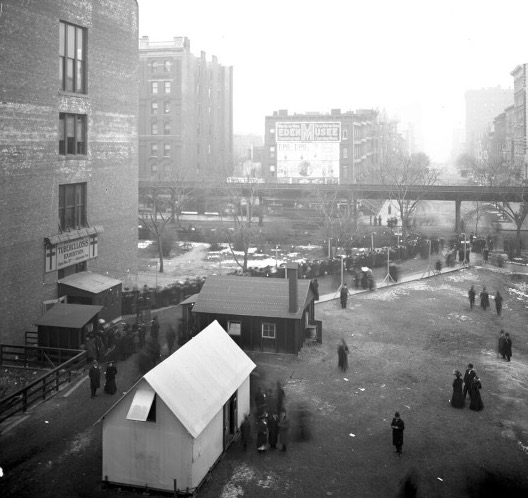

Visitors wait in long lines outside the Museum at the special 79th Street/Columbus Avenue entrance for their turn to tour the exhibition and the model dairy and cow shed in the foreground. Printed on the roof of the dairy in large letters that could be read from the street and elevated trains was the following: "MODEL DAIRY A Clean Shed Means Clean Cows and Clean Milk." The Museum had to remain open for 13 hours on weekdays (eight on Sundays) and to hire 50 extra guards -- in addition to the five policemen provided by the city to manage crowd control. The exhibition drew 753,954 visitors during its seven-week run, a record and 72 percent of the Museum's attendance of 1,043,582 during the entire fiscal year.

Visitors arriving to view the International Tuberculosis Exhibit, 79th St., American Museum of Natural History, December 1908.

New York State displays, International Tuberculosis Exhibition, January 1909. The temporary exhibition lined the walls and balcony of the Museum's newly constructed northwest wing.

From 1890 to 1920, tuberculosis was a leading cause of death in the United States, killing thousands and striking fear, especially among urban populations. The AMNH still continues to serve as a conduit of information on Public Health with temporary exhibits like Epidemic! The World of Infectious Diseases, February 27 – September 6, 1999, and The Secret World Inside You, November 7, 2015 – August 14, 2016.

More recently the Museum has sponsored lectures and educational programs online discussing the pandemic and Covid and hosted a popular vaccination site in the Hall of Ocean Life under the model of the blue whale where over 100,000 people received their vaccine.

For some addition new research on the piece see: https://www.amnh.org/research/research-library/library-news/curran-museum-archives

Written by Joel Sweimler and Tom Baione

![Howard Russell Butler's [Hydrogen prominences]](https://futureoftruth.media.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2921/2023/01/k6584-square.jpg)