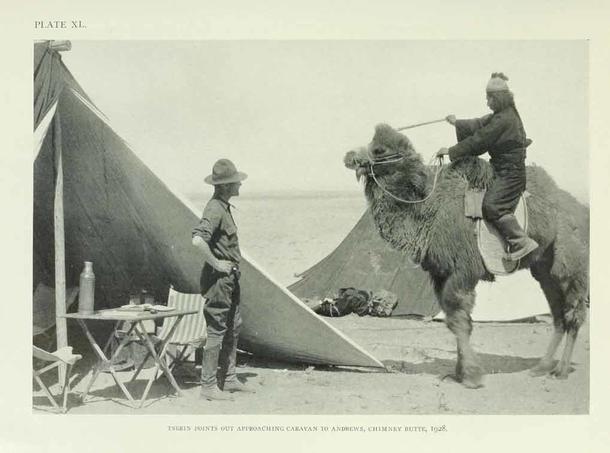

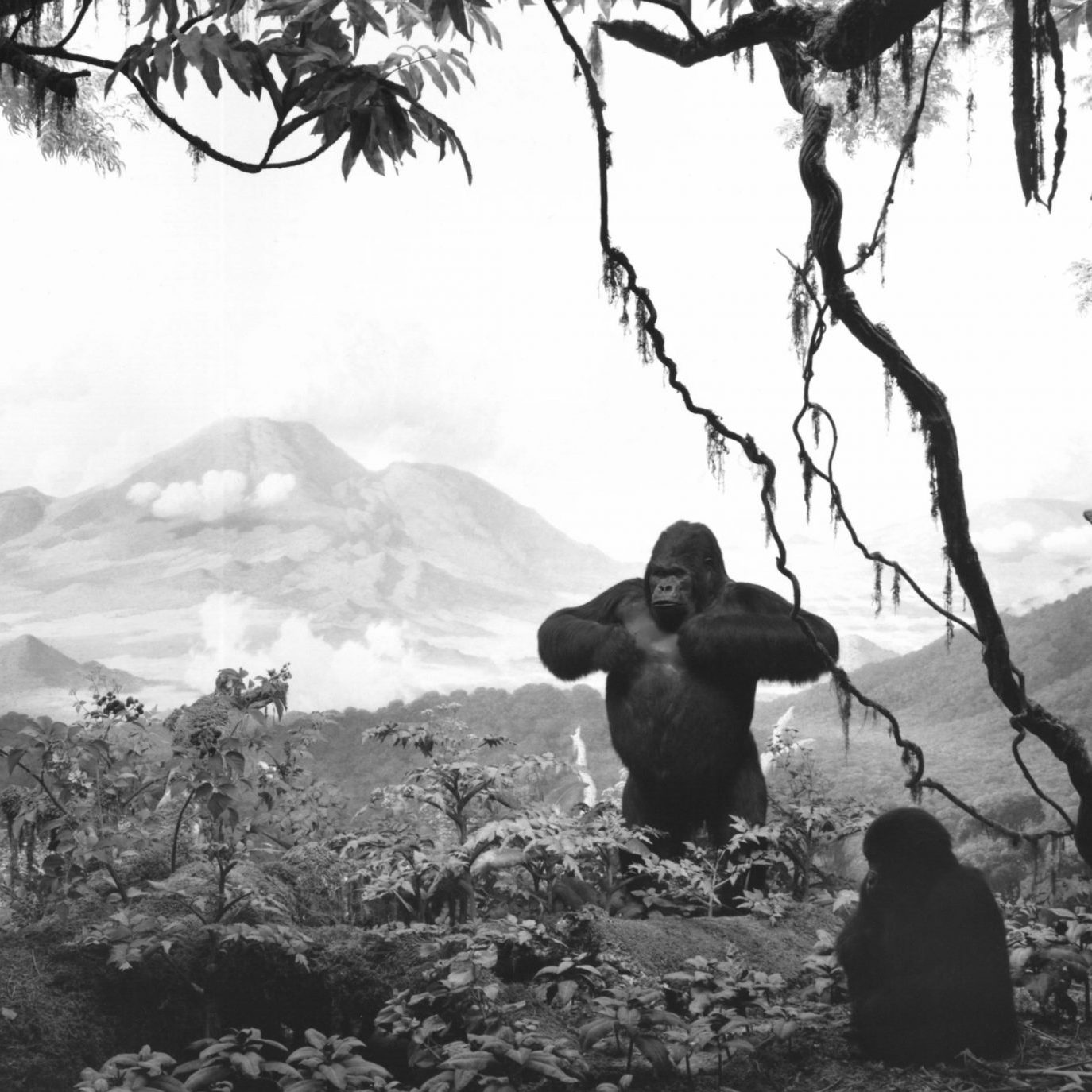

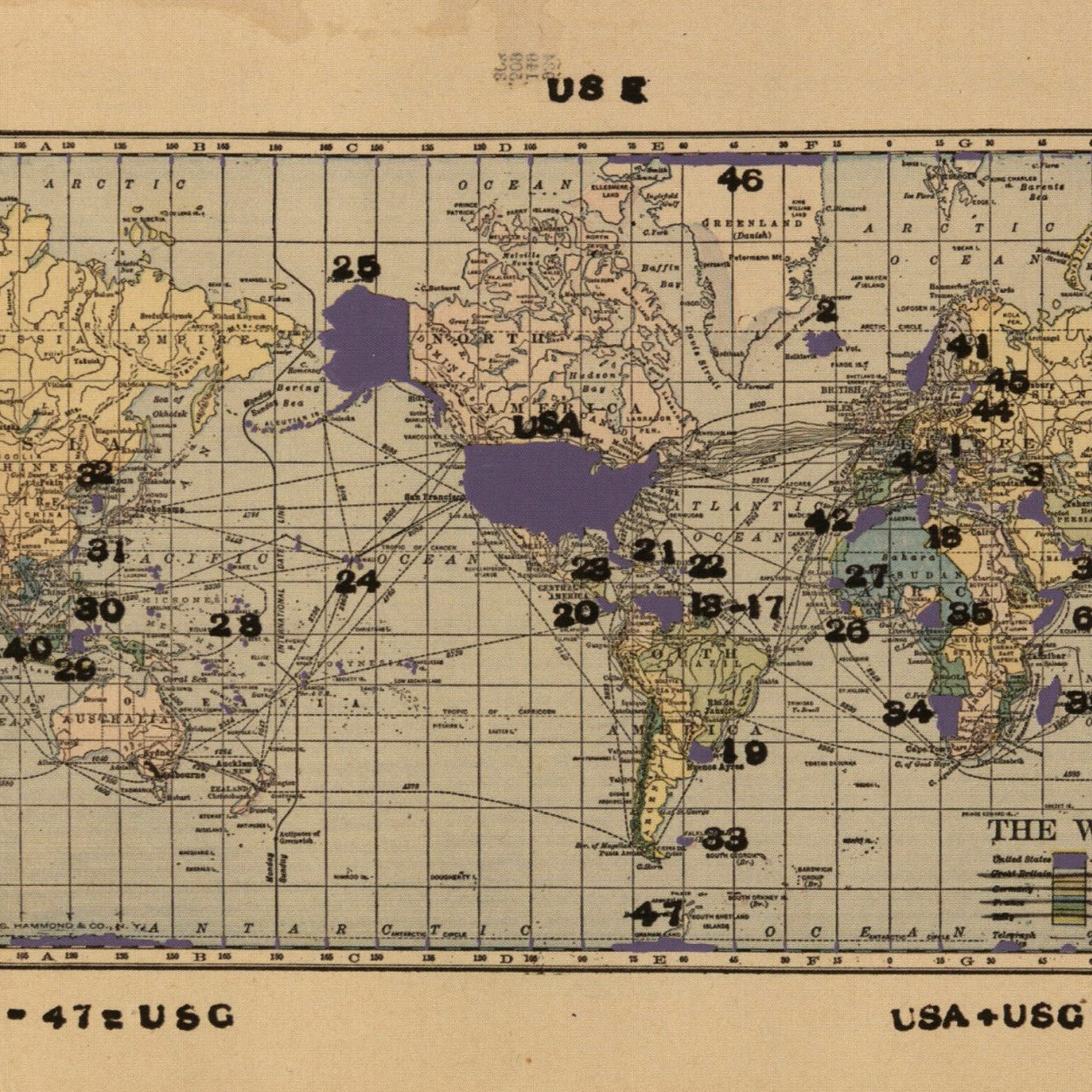

The American Museum of Natural History sponsored several expeditions to Central and East Asia during 1921–30. Asiatic expeditions were a massive undertaking. One expedition trip alone is estimated to have cost over $6 million in today’s money, and many failed to get off the ground due to a lack of funding. But the payoffs could also be huge. American explorer, naturalist, and zoologist Roy Chapman Andrews (1884–1960) led the AMNH’s team to uncover one of the world’s richest fossil deposits, preserved in the dry desert sandscape. The film reels were organized and compiled in the 1930s to commemorate a decade’s worth of exploration in Central Asia. The footage shows a partial recreation of the expedition’s most lauded discovery: a fossilized nest of dinosaur eggs. The twelve intact dinosaur eggs were wrested from the Flaming Cliffs in the Gobi Desert, located at the edges of present-day Mongolia and China.

In a New York Times article reporting the finding, reporters called expedition leaders, AMNH President Henry Osborn and Andrews, “adventurers of science." Andrews, in particular, looms large in the American imagination as an “adventurer of science,” because it is rumored that his perilous, globetrotting adventures were the inspiration for the beloved American film character Indiana Jones. Biographers describe Andrews as a “showman” who captured the hearts of an American audience through his many writings, which described his excursions, in addition to his scientific discoveries. The AMNH has contributed to the valorization of Andrews: “Andrews, who began his career sweeping floors at the Museum, eventually became the Museum’s Director.” Andrews did indeed become the AMNH President in 1934, following Osborn.

The film shown here illustrates one way the Museum disseminated knowledge and improved their public image. Films like this and the biographies written by Andrews contributed to a culture which romanticized and exoticized Asian culture and peoples. The narratives spun around the Asiatic Expeditions told of discoveries in new, foreign, and dangerous lands. Mongolian and Chinese people, especially as depicted in this film, played merely supporting roles as servants to American explorers. These narratives and representations fed an American audience with a taste for romanticized archeological expeditions, and helped to build public support and funding for AMNH's expeditions. This film and the history of archeological expeditions illuminate the interconnected mechanisms of power, money, and education all operating in concert to produce truth and knowledge.

Written by Katrina Kish

![Howard Russell Butler's [Hydrogen prominences]](https://futureoftruth.media.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2921/2023/01/k6584-square.jpg)