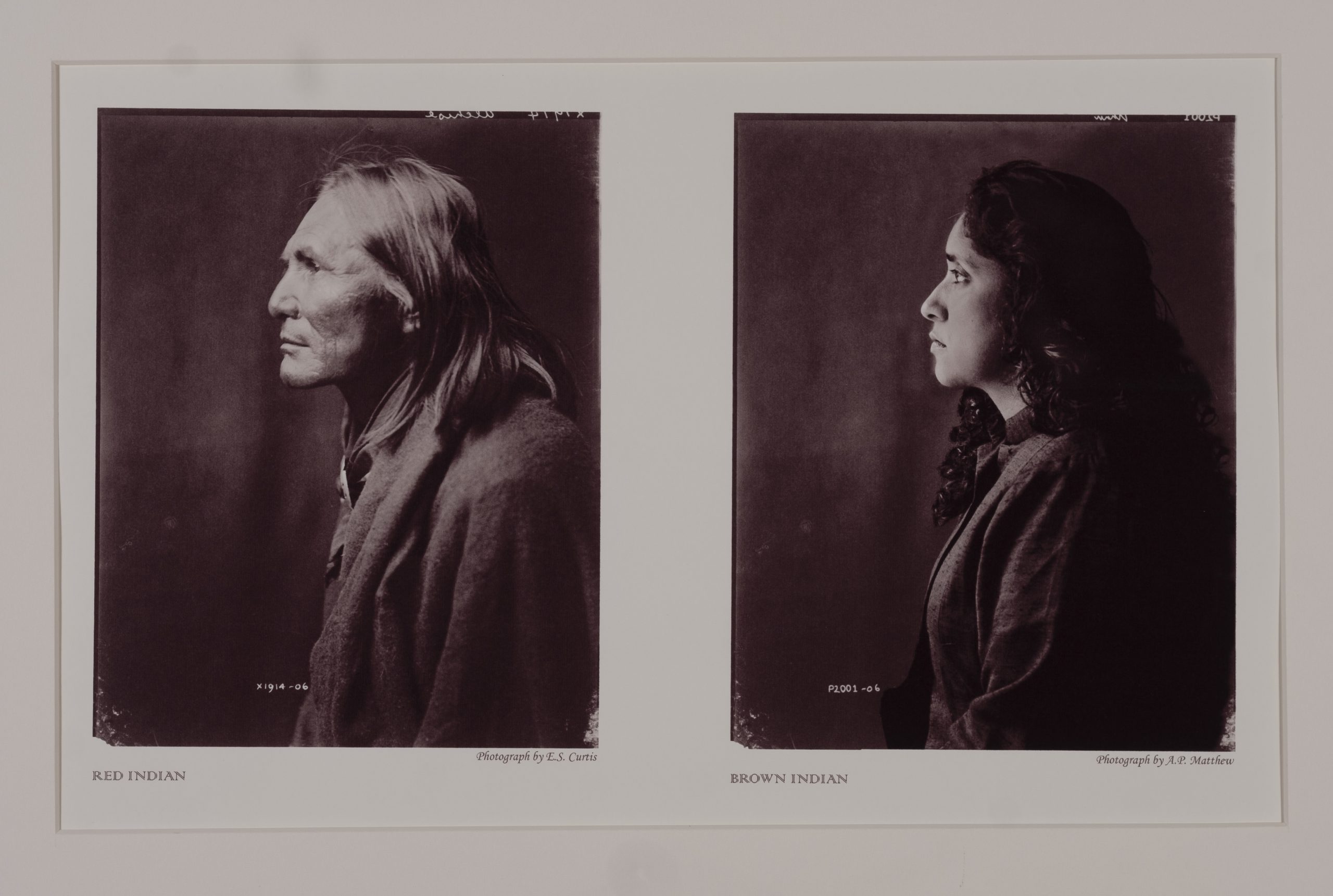

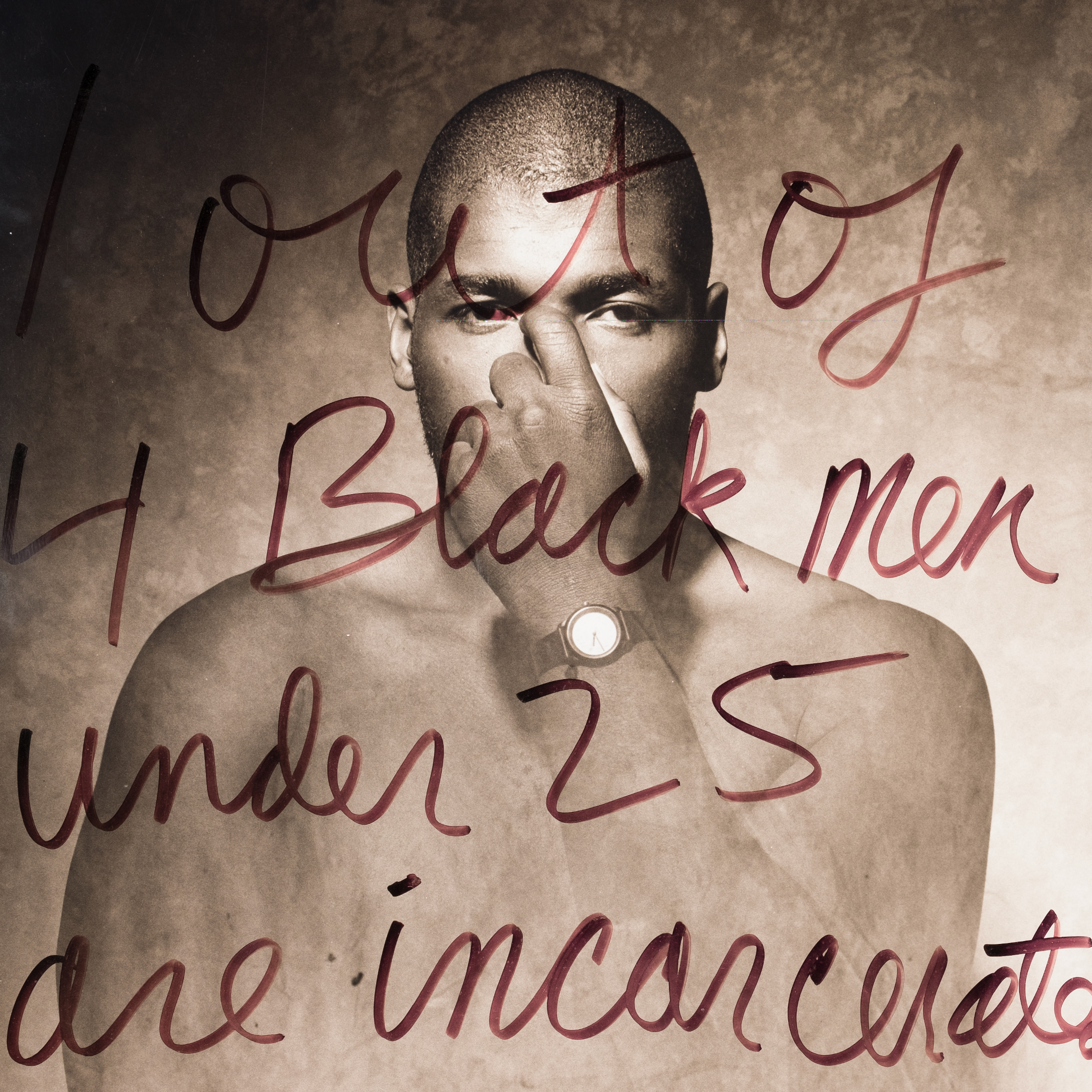

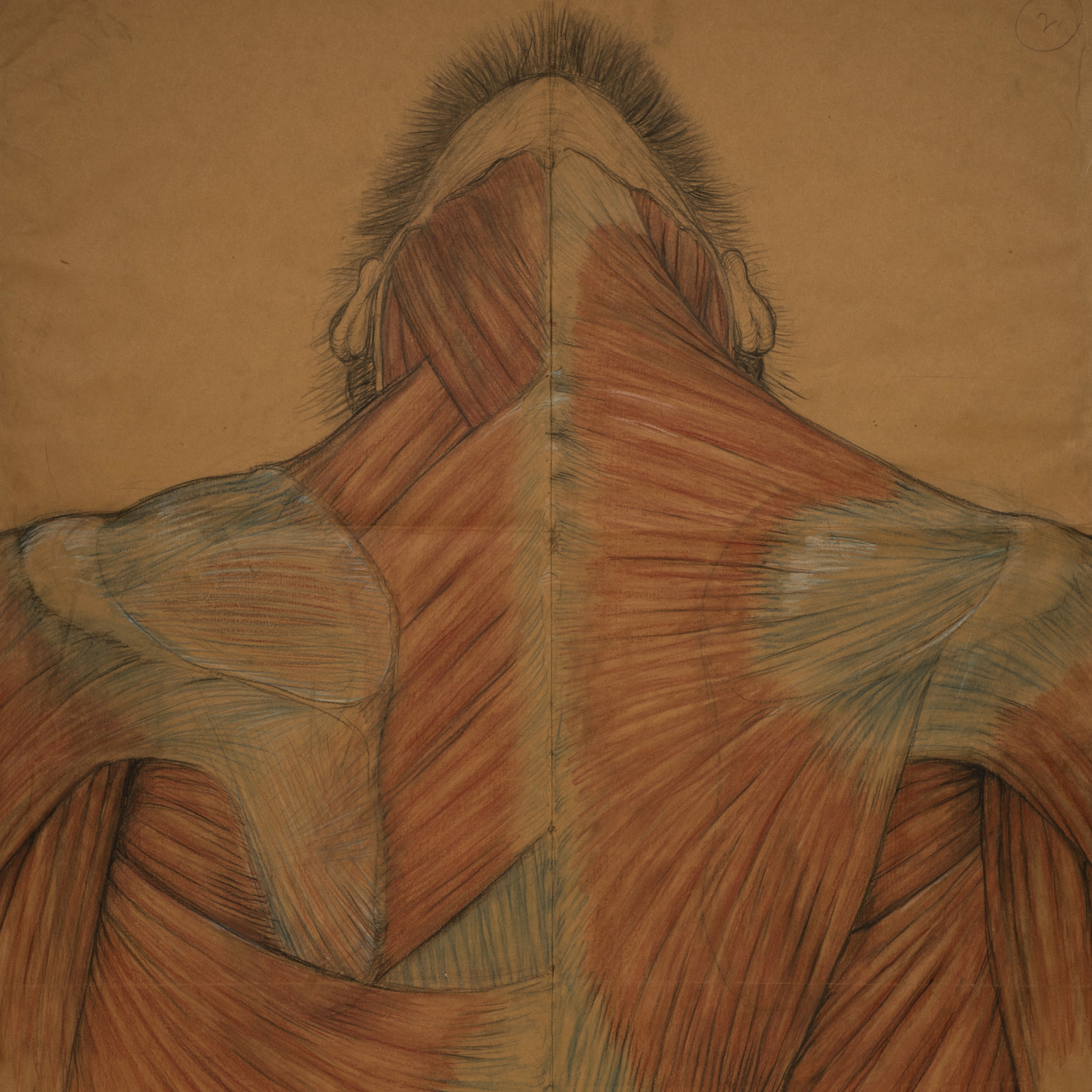

"Red Indian / Brown Indian" from the series An Indian from India (2001)

Annu Palakunnathu Matthew (Indian, born England, b. 1964)

Archival Digital Print

Contemporary World Art Fund, 2004.20

In this exhibition, we explore how often—in spite of attempts to create knowledge through objective and/or scientific means—“otherness” generates knowledge and interest. Western institutions encourage expeditions to “foreign” lands and while observation and interaction should promise new knowledge and understandings, often these interactions merely craft histories and images to satisfy Western tastes for exoticism, verify pre-existing prejudices, and support dominant power structures. “Red Indian/Brown Indian”, juxtaposes two stylized portraits: a self-portrait featuring the contemporary artist, Annu Palakunnathu Matthew which is paired with a portrait entitled “Red Indian” by Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952), celebrated American photographer and ethnologist. A contemporary with artists also in this exhibition, Thomas Moran and Timothy O’Sullivan, Curtis originally set out to capture the majesty of landscapes in the US West. While assisting on anthropologist George Bird Grinnell’s expedition to the Piegan Blackfeet Nation in Montana, however, Curtis became so deeply moved by the “primitive customs and traditions” of the Piegan people that he dedicated the rest of his career to documenting the lifeways of Native American Nations and peoples. Curtis’s images have a complex legacy and troubling relation to truth. He traveled with “prop” items and clothing that he collected and that we would add to portraits regardless of the tribal associations, culture, and beliefs of the people he was photographing. Therefore, while his portraits might seem authentic and like markers of people and their traditions, they need to be understood as his fantasies and imaginations about Native Americans. He also often depicted Indigenous peoples as dying out, fading away, disappearing into the landscape, which was again more about his attitudes and visions than a record of the people he photographed.

About her paired image “Red Indian/Brown Indian”, artist Matthew writes, “This work starts to question what is given credibility, what is patently contrived and how the two are not as far apart as we would like to believe.” Though we tend to view photographs as objective sources of truth which simply recreate reality, their perspectives are curated and artificial. Again, Curtis utilized several techniques to produce curated images including editing techniques to remove all traces of modern technology from his images. In addition to these editing techniques, his subjects don traditional clothing which had long been out of use, and they adopt poses which evoke nostalgic feelings of a primitive but dignified past. These manipulations create an illusion of distance and dislocation: it seems as though Curtis’s subjects existed long ago, well before the twentieth century. This perception can reinforce an attitude of apathy towards ongoing injustice. Matthew urges us to reconsider how much credibility we grant images like Curtis’s in representing the experiences of Native American peoples living under United States domination.

Additionally, Matthew’s comparison of “Red” and “Brown Indians” suggests that Anglo-Americans are to Native American Peoples as Britons are to Indian peoples: colonizers. One potent mechanism of colonial power is Orientalism. Edward Said, who first developed the theory of Orientalism, argues that Western colonizers produce knowledge about their colonized subjects which exotifies and objectifies them by casting them as “other”. This process of exotifying and thereby objectifying contributes to Western political, economic, and cultural domination. Other pieces in this exhibition also interrogate the role knowledge producing and preserving institutions, such as the AMNH and the Benton, have historically played in building on and profiting from Orientalism. Through lenses of Orientalism, Westerners consume exciting discoveries of ancient artifacts and stories of dignified but primitive people from long ago, rather than face the ongoing reality of oppression experienced by colonized peoples. Matthew’s project urges us to reconsider our understanding of our shared history and how we have created knowledge about ourselves and others.

Written by Katrina Kish and Alexis Boylan

![Howard Russell Butler's [Hydrogen prominences]](https://futureoftruth.media.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2921/2023/01/k6584-square.jpg)